A current affair

How two Walmart FLW Tour pros prepare for intermittent current flow

(Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the 2013 May/June issue of Bass Fishing magazine. To read more compelling articles from Bass Fishing magazine each month, become an FLW subscriber member. If you’d like to sign up for a digital subscription to access articles online, click here).

Early in his career as a tournament angler, Evinrude pro Dan Morehead became convinced he’d found the winning spot for an upcoming weekend event on Kentucky Lake. His premonition proved to be correct, as his ledge eventually produced 31 pounds of hungry largemouths. But it didn’t happen the way he’d expected.

“I knew the fish were there,” Morehead recalls. “But when I stopped there in the morning I didn’t get any bites. I came back around 10:30 and caught seven bass in seven casts and culled out everything I had in my livewell.”

A few years later, OFF! team pro Terry Bolton fished a Walmart FLW Tour event on the same body of water. Because he had an early boat number, he elected to stop at a ledge loaded with big fish first thing in the morning.

“In 45 minutes I caught one 3-pound bass,” he says. “I went into the creeks and caught my limit. Then I came back around 12:30 and quickly landed four 5-pounders and went from 15 pounds to almost 25 pounds.”

Different tournaments, but similar experiences for Morehead and Bolton: It was as if someone flipped a switch to make the fish bite.

Indeed, someone did flip that switch. It was an employee of the Tennessee Valley Authority who started generating hydroelectric power by drawing water through Kentucky Dam. In the process, he “juiced up” the bass.

Depending on how your tournament on an impoundment such as Kentucky Lake winds up, the person who makes the current flow or stop can be, in turn, your best friend or a heartless antagonist. And to some extent, the effects of current flow – or lack thereof – depend on your timing as well. The following sections describe how to make the most of intermittent flow, from those who know how to do it best.

High and low flow

When the person from the power company flips the magic switch, the effects aren’t immediately apparent everywhere throughout a lake. If you’re near the dam at either end of an impoundment, you’ll be able to see and feel its impact almost right away, but in between there might be a slight delay, although you should expect to feel the current kick in quickly. Any variance typically hinges on the shape of the reservoir at issue, and similar generation levels might not affect all lakes the same way.

For example, Bolton says 20,000 CFS (cubic feet per second) of current flow is a “drop in the bucket” on Kentucky Lake, but on neighboring Lake Barkley, it might be enough to make bass bite. A lot of it has to do with the lake’s width and basic physics. Where a lake is big and wide, as Kentucky Lake is on its northern end, a given amount of generation might only provide a small amount of current, but where the water starts to neck down, there’ll be more felt current.

It’s also important to pay attention to both ends of an impoundment. Typically, it takes longer to see the benefits of flow from the upriver dam than the downriver dam.

“You need to know how much water is going in and how much water is going out to understand what is really going on,” Morehead explains. “You also need to pay attention to when they (damkeepers) are shutting the current off. When that happens, the lake comes up and the fish suspend.”

Whether it’s barely moving or ripping hard, current is always your friend – the more, the better, up to a point. Morehead explains that as far as the fish are concerned there might not be such a thing as too much current, but in some instances an excess can make it tough to fish, especially deeper than 20 feet.

“When it’s really rocking and rolling, and you have a spot that a crankbait won’t reach and you can’t keep a spinnerbait down,” Morehead says, “you might have to fish a jig or a worm. And it’s just like hunting – you have to lead them and use the current to get your bait to them.”

In that situation, reservoir fishing takes on an air of river fishing, by using the flow of water to deliver the lure to the fish by casting slightly upstream.

Slack-to-fast strategy

On tidal rivers, the effects of the moon’s gravity are measurably predictable, and it’s possible to “run the tide” to find optimal water levels. Both Morehead and Bolton say that with a lot of generation statistics and some careful modeling it might be similarly possible to follow the current’s effects as it courses through a reservoir, but in reality their tournament game plans are simpler than that.

On tidal rivers, the effects of the moon’s gravity are measurably predictable, and it’s possible to “run the tide” to find optimal water levels. Both Morehead and Bolton say that with a lot of generation statistics and some careful modeling it might be similarly possible to follow the current’s effects as it courses through a reservoir, but in reality their tournament game plans are simpler than that.

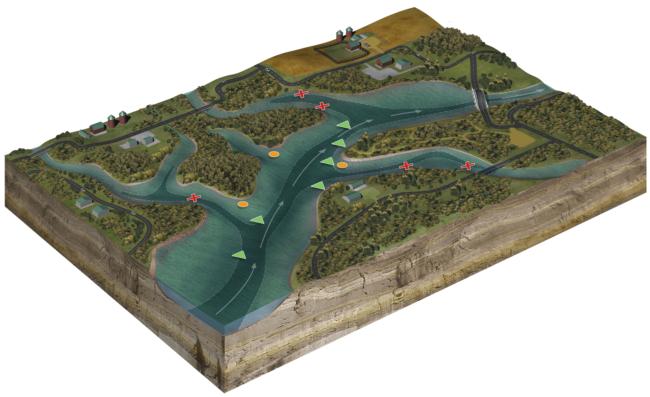

In a typical scenario, they’re not prepared to run from one end of the lake to the other in the course of a few hours. Instead, they try to pick the section of the lake that they believe holds the most quality bass, and then divide it into roughly three types of spots: places that are not current-dependent, places that feel the current’s impacts most quickly and places that will come into their own when the flow hits its stride.

No current needed

When the current is slack, bass and baitfish on the main lake tend to suspend out in the river channel. They spread out and become less active. It’s at these times, usually in the mornings, when both pros focus on bass in creeks and bays.

“There are certain places on a lake that are 90 percent current-dependent,” Bolton says. “It really affects the ledges closest to the river channel, so if I know that it won’t kick on until 10 or 11 o’clock, I’ll start on creek-type ledges. They don’t seem to need the same amount of flow to generate bites.”

High-impact areas

Once the current starts to move, Bolton tries to intercept what he hopes are newly active bass in the places most impacted by the current. On a typical lake that flows north-to-south, he’ll look for points on the main river channel that face north. On Kentucky Lake, which flows the opposite way, he’ll look for points that face south. As the current becomes steadier, he’ll branch out to other ledges that he expects to hold schools of fish.

Heavy-flow strike zones

As the current becomes steadier, and more equally distributed along the river channel, the angler is confronted with a choice: If he can keep the school fired up on one of the initial impact zones (such as points facing into the current), then he can stay there as long as the bass and baitfish remain active. Otherwise, he has the option to go to spots that might be more subtly attractive – perhaps a less-defined point, or one facing in the wrong direction, or even a small shell bed on a straightaway.

According to Morehead, the structural elements he looks for change depending on how far into the postspawn period the bass might be.

“Early in the season, before the fish are really beat up, I’ll look for a 90-degree turn (in a channel edge) or a defined point,” he explains. “But later in the year, when the fish are highly pressured, I try to key on little shell beds, drops or isolated stumps.”

Electricity needs

The other element an angler must take into account, particularly when planning for a multiple-day event, is the changing nature of generation schedules, which are dictated by electricity needs and lake use.

“Generation has changed over my lifetime,” Bolton says. “Except in very high water conditions, like rain events, there’s not much water pulled on weekends anymore.”

Accordingly, the milk run that paid off during the week might need to be tweaked, or abandoned altogether, once Saturday rolls around.

Fish positioning

Good electronics, with both 2-D and side-viewing sonar, are especially helpful in locating not only the key structural elements that are exposed to the current, but also in determining how fish and prey relate to that structure.

“Terry and I have talked about it many times,” Morehead says. “We always idle around a spot before we fish it. If you see bass or baitfish that are suspended, they’re probably not pulling water.”

In that case, the fish likely won’t be active, but Morehead has learned to create artificial flow that sometimes gets the fish feeding.

“Get your boat half up on plane to where it’s really plowing and digging, then do some figure eights to stir up the water column,” Morehead says. “A lot of times before you can come off pad the fish will be schooling in the water column.”

Morehead saw the same effect during the 2012 Forrest Wood Cup on Georgia’s Lake Lanier, where even during the dog days of summer boat wakes and wind current made a difference in the bite.

Bolton has noticed that bass occasionally do other things besides suspend in times of low flow. They’ll also stage at the base of the ledge in an inactive mode. Rather than dragging a jig or worm in front of them, sometimes those fish can be enticed to strike with a smartly hopped lure – thus the development of the “jig stroking” pattern on Kentucky Lake and the more recent rise in popularity of the flutter spoon throughout the country. Once the flow begins in earnest, though, he’ll make his initial pass on a spot on the top of the ledge where the fish tend to feed most actively. If he doesn’t intercept them there, on his next pass he’ll back way off to see where the bass and bait have congregated.

Even if he’s located the depth they’re using, Bolton will continue to experiment with a variety of lures – football jigs, big worms, crankbaits, swimbaits and spoons, to name a few – to keep the school fired up. As a general rule, the heavier the flow, the more aggressive the presentation should be.

Seasons and reasons

While Morehead’s and Bolton’s strategies for intermittent current flow focus on the summertime, when TVA impoundment bass tend to gang up on well-defined ledges, the pair says that understanding the role of current can be critical year-round.

While Morehead’s and Bolton’s strategies for intermittent current flow focus on the summertime, when TVA impoundment bass tend to gang up on well-defined ledges, the pair says that understanding the role of current can be critical year-round.

“I’m convinced that current plays a role at any and all times, even in the early spring (when a lot of bass are shallow),” Morehead says.

Bolton agrees, recalling a Kentucky Lake Walmart FLW Tour event in May 2006 when he came in second to Alabama pro Steve Kennedy. The lake was extremely high, and while some fish were still spawning, the dam was wide open. That caused a lot of big fish to position at current breaks.

Similarly, he’s seen current play a big role on the far side of summer, during the fall. Every five to seven years, when the remnants of a hurricane come sweeping up from the Gulf of Mexico and deluge the Tennessee River valley, Kentucky Lake is raised to unseasonable levels.

“That’s usually when we’re in the drawdown,” Bolton says. “The TVA doesn’t like water in the system at that time of year so they’ll dump it out as fast as they can. When they’re moving 300,000 or 400,000 CFS through Kentucky Dam, the lake becomes like a gigantic river, and you have to fish it like a river. The bass are more bank-related than they are during the summer, but you still run around looking for points that allow the fish to sit just outside of that current.”

Moving sources

The importance of current isn’t just limited to reservoirs with power generation; it’s equally applicable on just about any body of water. Morehead says he’s taken the knowledge developed on Kentucky Lake and applied it to a wide variety of other waterways as well.

“Current is the key to success on a tidal body of water like the Potomac,” he says. “Those fish will line up by riprap or a log – anything that creates an eddy pocket. The only thing that’s different on a lake like Kentucky Lake is that you can’t see the eddy pockets. I’ve also used it on lakes such as Ross Barnett (Reservoir), where I’ve gone way up the rivers. It’s all pretty much the same thing. The bass don’t want to expend a lot of energy in order to feed.”

Getting the 411

Anglers have long relied on generation schedules, as the information is helpful in the development of a tournament strategy. Such information is still available by telephone, but the Internet and smartphones have made the process much simpler and more immediate.

For example, to learn the schedule for Lewis Smith Lake, the second stop on the 2013 Walmart FLW Tour, anglers checked the website of Alabama Power, which operates multiple dams on the Warrior River. A multitude of information about the lake’s conditions can be found at lakes.alabamapower.com. Similarly, information for stop No. 3 at Beaver Lake in April was found on the website of the Southwestern Power Administration, swpa.gov/generation.htm.

The TVA has an extensive listing of information about its many waterways available on its website at tva.gov/river/lakeinfo/index.htm. There’s even an app for both iPhones and Androids, available at tva.gov/mobile/index.htm.

Even if you have an up-to-the-minute report on expected generation schedules, it always makes sense to keep an eye out for any deviations from the plans. If water-release schedules unexpectedly change, failure to notice could wreck your dreams of glory.

Related links: