Jigging Spoons for Winter Bass

A simple slab of lead is a cold-weather classic

It doesn’t get much simpler than a jigging spoon – some lead, a bit of wire and a treble hook. That’s it.

Its simplicity in form is mirrored by the ease with which it can be fished. Just cast it out or drop it straight down, then hop the spoon a few times. The result: You have a near-perfect shad-in-distress imitator.

Of course, the application of the spoon hinges on finding bass in the first place, which is the biggest challenge. Walmart FLW Tour pros Jason Johnson and Clark Reehm are experts at finding winter bass in their respective regions of the country and offer FLW readers some advice on where to look and how to get them to bite the spoon.

Johnson Targets Spots in Timber

When and where

“I think anywhere with big water and clear water, the jigging spoon comes into play in the wintertime,” says Johnson, a Tour sophomore.

Most of his winter fishing experience has been spent targeting spotted bass in mountain reservoirs such as Lake Lanier near his Georgia home. He usually finds them suspended in standing timber where there are threadfin shad for forage.

“One of the reasons the jigging spoon is so popular in the South is that we have a ton of threadfin shad,” Johnson adds. “In the wintertime, like on Lanier, which is a blueback herring lake, bass transition to where they don’t want to chase the bluebacks. They [bluebacks] are so fast and tend to go out to the river channel in the wintertime. The bass switch, and all winter long their forage is threadfins. Those fish are down there waiting on the threadfins to die off or swim by, and the spoon is a perfect imitation of a threadfin.”

How fish are positioned is important for bait selection too. If they’re tight to bottom within the timber, a drop-shot is less likely to snag on the way down. If they’re within 15 feet of the surface in gin-clear water, they could be spooked by the boat overhead, making a horizontal approach with an under-spin a better option. When they’re suspended in that “in-between” range, however, a vertical approach with the spoon is often the best choice because it gets down faster and draws bites from aggressive bass.

“In most of the deep impoundments in the South, a lot of times the fish will be up in the top of the natural timber,” Johnson explains. “They might be suspended over 40 to 60 feet of water, but they’re only 20 to 25 feet deep.”

Locating fish

Finding suspended bass can be a trial, though once you find them, usually they’re schooled together and you can fish that school through the season.

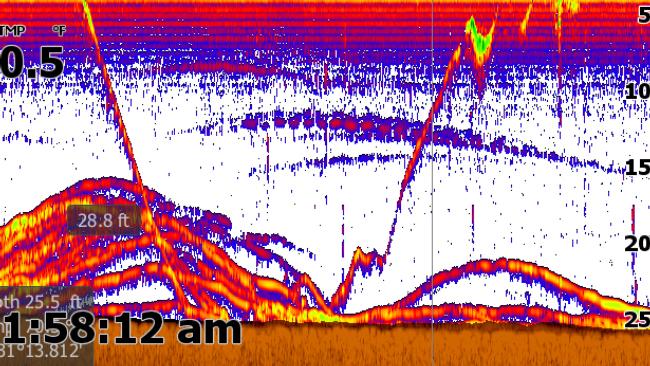

In winter, Johnson searches outside the mouths of creeks and coves where bass will spawn eventually. High-percentage targets include the first timber edge outside those creeks, or points and other irregularities within the timber. Usually, a timber edge will form alongside a channel, where the trees once grew along a creek bank before the lake was filled. Also, in some instances, trees were cut off above a certain elevation before the reservoir was flooded, leaving an inside edge between the remaining timber and the shore. Where Johnson finds one of these edges, he idles in a zigzag fashion along it to scout for fish with his sonar. He says it’s rare that bass will set up at random in the middle of a vast forest of standing timber.

Roadbeds are also classic winter targets, as are ditches or drains that course across large flats or out of spawning pockets. Johnson finds many of his best drains by simply scanning the hilltops. Where a valley or “holler” splits two hills, water flows down into the lake. Sometimes the low-lying contour continues out underwater, or the inflow carves a small ditch in the lake floor. Either way, bait and bass congregate in these areas.

In all of these examples, of course, the common factor is the presence of baitfish.

Choosing spoons

Johnson has settled on the Berry’s Flex-It Spoon as his go-to choice. He likes 1/2 ounce for most situations, but suggests that the best guide is to use the lightest spoon possible for the depth being fished, or to match the dimensions of the spoon to the size of the shad in the area.

“If you do want to throw them something different, the lead is soft, so you can bend it and put arches in it and make it flutter and roll around a little more as you jig it up and down,” Johnson says of the Flex-It. “I always start out with a straight spoon. If it’s not happening or they’re following it but not getting it, you can bend it one way or the other.”

Jigging action

“My favorite way to fish it is to use a fairly parabolic rod, so when I’m popping it the rod’s not ripping it real hard, but the rod is loading up,” Johnson says. “I tend to do 10- to 12-inch rips four or five times in a row and then let the spoon sit. If you use a swivel, when you let it sit the spoon will spin in place.”

The swivel is used to connect the main line to a leader of the same line a couple feet up from the spoon. Johnson prefers 12-pound-test fluorocarbon for fishing near the tops of trees and 15-pound test when he needs to work down through the branches a little farther – keep in mind that he’s fishing very clear water. His rod is a 7-foot, 1-inch, medium-heavy model teamed with a high-speed baitcasting reel.

“I usually drop straight to the depth they’re suspending,” he adds. “Usually in wintertime if I’m on a decent school of fish, a pretty aggressive one is going to bite on that first drop. That kind of sets the stage for whether they want it or whether I’ll have to work with them or change up to get them to bite.”

If the fish don’t seem interested, he changes the cadence, the length of the pause or the length of the rip in hopes of eliciting a strike.

“If they’re sitting there staring at it and won’t commit, I just burn it all the way back up almost to the surface, then drop it all the way back down past them,” Johnson says. “Then I bring it back up to them to try to get their interest back up. It’s a total reaction bite.”

Reehm Rips the Spoon Year-Round

Fishing for Efficiency

In his years as a guide and tournament angler at Sam Rayburn in Texas, Clark Reehm has perfected the art of casting a jigging spoon to bass, and not just in the winter.

“At Rayburn that’s what I’m kind of known for,” he says. “I fish it almost year-round, from mid-April to the end of February. It’s actually more versatile than people think.”

Reehm throws a 7/8-ounce War Eagle Jiggin’ Spoon, which comes with a built-in swivel and premium hook. He fishes it with a Daiwa Tatula 7:1 retrieve ratio reel and a Dobyns Champion Series 704 medium-heavy, fast-action rod. He says any rod used for a spinnerbait is probably just right for the spoon.

For line, Reehm employs 15-pound-test Seaguar InvizX fluorocarbon for open water and heavier 20- to 25-pound test for fishing brush piles.

Tackle aside, the reason why Reehm uses the spoon so often is that any feeding predator fish can’t resist it – he catches white bass, yellow bass, drum and catfish on it too – and it can be fished fast, without wasting time re-rigging after a catch.

“It’s about finding fish. If you find them, or you find shad there, there’s nothing in your tackle box as efficient at catching them as the spoon,” Reehm adds. “The only thing you’ve got to worry about is if it’s kinked or foul-hooked. If that happens, reel it in. I probably catch 5,000 to 10,000 fish a year on a jigging spoon out here.”

Casting versus dropping

Some days, a vertical presentation is better than casting, and not always for an apparent reason. Reehm also will drop vertically on precise targets – say, a brush pile or small hard-bottom area.

“I’m not necessarily video gaming, which is more for suspended fish,” he says. “If I see fish on the bottom I just start ripping it. I start popping it around for a minute and then lift it back up. A lot of times they want that fresh drop. I give them about three drops. If they’re there, they’re going to eat it. If they’re lethargic and on isolated cover, and I think one big one is there, I might play with them. But if they’re there to feed, they’ll bite.”

More often, however, Reehm uses a casting presentation, which is better for covering water and doesn’t require him to park over the fish. They usually aren’t deep enough for that approach.

“If I get on a drop or point or pond levee or hump, I’ll cast the spoon out there and hop it back like worm fishing a lot of times,” he says. “I can cover different water depths and work it through the water column.”

On a typical cast, Reehm lets the spoon hit bottom, cranks the line until it’s tight and then starts to hop the spoon back, letting it fall on a semi-slack line. He experiments with the force of the hop to find what works – sometimes sweeping it, other times just shaking it across the bottom.

In other situations – perhaps to stay above a brush pile or catch fish that are looking up – Reehm counts down the spoon after it hits the surface and works it in the middle of the water column. With a 7/8-ounce spoon, a three count gets it down about 10 feet, a four count to 12 to 14 feet deep and a five count to 15 to 18 feet deep. The countdown method works whether he’s casting or vertical jigging.

Finding the feeding spots

Reehm has spent enough time on Rayburn over the years that he knows plenty of places that are traditionally good “feeding spots” where threadfin shad attract all types of predator species. Most anglers know of a few similar places on their favorite fisheries as well. These might be community holes, or those go-to spots that are fished throughout the season because the bait and bass are periodically there.

“If bait is in such areas, those are natural feeding spots where the bass will pile up,” he says. “It’s just like a watering hole on the African savannah. If animals are going there to water, you’re going to have lions there too.”

On Reehm’s home fisheries, hard-bottom areas such as shell beds or flooded roads are good targets because the bottoms are primarily clay. He locates roadbeds using maps of the area from before the lake was flooded. Pond dams and brush piles are also good man-made targets.

Natural structure includes the deep edges of main-lake flats, points, channel swings and any kind of drain where water was once flowing across the landscape.

Reehm scans each area before fishing. Sometimes it’s obvious that a school of bass is using the area, though bass are sometimes so tight to the bottom that they don’t show up well on the graph. He might still stay if it’s a spot where he’s caught fish before, and he definitely stays if he sees shad, which often school in giant “clouds.”

“In the wintertime down here, on Toledo Bend and Rayburn, the right fish sit on the bottom,” says Reehm. “I’m not going to look for fish suspended in the middle. There are better ways to catch them [suspended fish] in the wintertime, primarily with an A-rig.”

While umbrella rigs and jerkbaits will continue to get plenty of use from anglers in the coming weeks, take some advice from Johnson and Reehm and give the simple jigging spoon a few casts. If he gets on the right fish, a few casts might be all it takes to convince an angler that it belongs in his winter arsenal.