Fishing grass mats with Randall Tharp

Angler: Randall Tharp

Date: Oct. 24, 2011

Fishery: Lake Guntersville

Fishery Type: Tennessee River

impoundment with regular current

Primary Structure/Cover:

matted milfoil and hydrilla

Primary Forage: shad, bream

Water Temperature: 62 to 68 degrees

Air Temperature: 50 to 75 degrees

Water Clarity: slight stain

Weather: partly cloudy; winds 5 to 10 mph

EverStart pro Randall Tharp is an all-around juggernaut when it comes to power fishing, especially on grass lakes where he can get back to his roots of frogging and flipping for giant bass.

Which is why I jumped in the boat with Tharp at Lake Guntersville last fall for a lesson in how to break down matted grass and how to catch big, buried-up largemouths. Trust me, there wasn’t a spinning rod in sight.

Quit Buggin’ Me

We start our day flipping in a mat adjacent to the main river channel. Within minutes of stopping, we are engulfed by swarms of gnats. It’s not swarms of Biblical plague proportions, but it’s annoying enough. As I’m swatting, I notice that Tharp seems unfazed.

“I love them,” Tharp says. “Every time I come out here and the bugs are buzzing, I catch bass. I’ve been out here before where you had to wear something over your entire face because the gnats were so bad.”

The logic is sound. Bugs draw feeding bream, and bream draw big bass. Suddenly, the buzzing doesn’t seem so loud.

Through the Roof

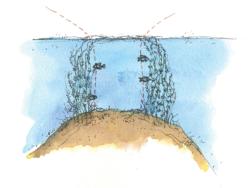

Although the grass mat appears to be a tangled, knotted mess, it’s only the canopy that is actually thick. The matted grass visible along the surface topped out earlier in the season and cut off the sunlight that the grass below it needs to keep growing. The result is a hollow space that’s covered above by the mat, and below by a floor layered with dead grass blocked off from the light.

Although the grass mat appears to be a tangled, knotted mess, it’s only the canopy that is actually thick. The matted grass visible along the surface topped out earlier in the season and cut off the sunlight that the grass below it needs to keep growing. The result is a hollow space that’s covered above by the mat, and below by a floor layered with dead grass blocked off from the light.

When the grass mat is on a drop-off or sloping area, emergent, live grass grows on the deep side, but hasn’t quite topped out. This hard edge of grass creates a wall, and the canopy creates a roof. Tharp explains that the key is to pitch through the mat right along the hard edge, because that’s where the bass will be holding and will have the best opportunity to see the lure.

Don’t Bother

We continue pitching the grass canopies, and on about our third stop we pull up to the backside of a grass mat, opposite the main river channel.

“I was catching them good flipping here the last few days,” Tharp says. “They should still be here.”

As we work our way along, both of us pitching at the hard edge of the mat, I notice that several times when Tharp pitches his Zoom Z-Hog out it gets stuck in the mat. Instead of working to get the lure through, he just brings it in and makes a new pitch. I ask about this.

“If you come out here and fish all day and count the number of bites you get shaking it through and the number you get when it falls through clean, you’ll see there are a lot more when it falls through,” Tharp explains. “It’s a waste of time to try and shake it through when you could have made two more pitches in the same amount of time.”

Listen Up

After catching only a couple small fish flipping, it seems as if the day might not go as planned. But then, Tharp turns to me and asks, “Do you hear that?”

I stop and listen. For a second, I think I’m at the breakfast table pouring milk over Kellogg’s Rice Krispies. A constant snap, crackle and pop ring out in front of us under the mat.

“That’s where my flipping fish went,” Tharp says as he kicks the trolling motor on high and powers into the mat. It’s not the bass we hear, but the bluegills sucking little bugs off the grass just beneath the surface. According to Tharp’s theory, the same noise we heard has likely drawn the bass deeper into the mat.

Stay Awhile

Once we set up shop in the heart of the mat, Tharp begins to break down all the grass within reach with a black frog. I, too, throw a frog.

“Generally I move my cast about every 10 feet, then come back and split those trails,” Tharp says about his thorough approach etched in the weeds.

He catches a small keeper in the first few casts, but in another 20 minutes without a bite I start to get bored with this location. Then Tharp turns and throws his frog directly where I had been working mine. A 3-pounder blasts through the mat on the first cast.

He catches a small keeper in the first few casts, but in another 20 minutes without a bite I start to get bored with this location. Then Tharp turns and throws his frog directly where I had been working mine. A 3-pounder blasts through the mat on the first cast.

As a self-proclaimed “exceptional frog fisherman,” I’m a bit taken aback by his showing me up, but I chalk it up to luck and continue plugging away in a new direction. Turns out, there’s no luck involved.

Tharp catches two more bass from my previous spot, then swaps over to my new location and hammers a few more. Serves me right – at some point, I had given up, and thinking you’re not going to catch any fish usually means you’re actually not going to catch any fish.

Tharp’s competitive side gets the better of him. He starts rubbing it in with a big grin as he notes that he has me down 10 to two. I decide to let my pride take a hit and stop casting for a few minutes to watch the master work.

He fires out a cast as far as he can and then slowly, slowly works the frog back. His rod tip twitches in bursts of six, then pauses for five to 10 seconds at a time. Looking in the direction of his frog I can’t tell it’s moving until it’s within 30 feet of the boat.

Taking note, I heave out my frog. As I begin to retrieve it I make a conscious effort not to move too far, too fast and force myself to let the frog sit for an eternity at a time. After firing at one spot for three casts, a 4-pounder explodes on the frog on about the seven-count of a pause.

Bowed up, I drag the fish in through all the muck and mat, then casually inform Tharp that this “tournament” is no longer about catching the most fish, just the biggest.

Weigh it Down

After sitting in the one spot and catching fish after fish for about an hour and a half we finally take off in search of something new. On our next stop Tharp has a massive blowup and feverishly hauls in a bass in the 4-pound range.

At this point, our little competition is in full swing, but Tharp humors me by divulging a few more of his frog-fishing tips.

Shaking his frog he asks, “Hear it?”

Something inside the frog rattles.

“It’s split shot,” he says as he pulls a couple more from his pocket. He shows how he pushes them through the hook hole of the hollow-bodied frog in order to add more weight.

“You see how thick that slime is?” he asks, pointing to the thick layer of sludge atop the mat. “This frog will actually sink if you set it in the water, but the added weight makes it cut through that slime so the fish can find it.”

Pulling our frogs through the same patch of slime, I can tell that his is leaving a deeper, more defined trail.

Repetition, Reward

Working a mat, Tharp suddenly spots a blowup and fires to it. The frog lands within a foot of the hole, but when he works the frog back across it, nothing. He reels in and casts again, plopping the frog down within a foot of the hole for a second time. Still nothing. This goes on for about six casts over 10 minutes, and then finally the mat actually rises up and the frog disappears in a swirl of green weed and white water. A swift, strong hookset brings a 4 1/2-pounder flying up through the mat. Patience paid off, and persistence won the fish.

“Sometimes you just have to pester these fish into biting,” Tharp says. “If I miss a big one I’ll throw on it for 30 minutes. And eventually, he’ll bite.”

Tharp explains how the fish never left the spot he was in and likely saw the frog each time it came by. Reluctantly it ate the lure out of pure frustration.

We spend the rest of the day this way – his patience paying off with big fish, and me taking the proverbial butt whuppin’. But I learn an invaluable amount about breaking down a mat bite with a frog.

We spend the rest of the day this way – his patience paying off with big fish, and me taking the proverbial butt whuppin’. But I learn an invaluable amount about breaking down a mat bite with a frog.

Tharp’s strategies require you to slow down and ignore a few of modern tournament bass fishing’s conventions, primarily that you have to be constantly on the move and covering water. The results, however, speak for themselves for this big-bass, matted-grass expert.

Lessons Learned

• Target the “hard edge” formed where emergent grass walls up alongside a matted grass canopy when punching large beds.

• Listen for the sound of bluegills feeding on insects. Where you find bluegills, you’ll find grass bass.

• Once you find an active mat, stop and work slowly with a frog. Line up casts side-by-side and make repeated presentations. Work it slowly with frequent pauses.

• By dropping a few split shot into the frog’s belly, it’ll not only rattle, but will also create a deeper profile in the mat that make it easier for bass to find.

• If you see a bass blow up, or if one misses your frog, throw back to that spot over and over. It might take 30 minutes, but the fish should bite again.