Slow-rolling along

Weed-free and capable of the big bite, the jig just got a little more versatile

Editor’s note: This article is from FLW Bass Fishing.

——————————————-

Versatility is everything in bass fishing.

One-trick ponies, capable of dominating a particular event with a trademark tactic, often turn into one-fish ponies when the conditions or location changes.

That’s part of what makes a jig one of bass fishing’s most effective lures. It’s as versatile in its uses as a top pro is in his ability to make multiple presentations work.

You’ve heard of swimming a jig, the technique of burning a jig near the surface that can be deadly for big bass relating to shallow cover. And you’ve heard of dragging a jig, which is perfect for scraping big bass off deep structure.

Slow-rolling a jig falls somewhere in between. The ability to bounce and roll a jig along bottom on a straight retrieve for a reaction strike is a powerful tool for covering water and fishing depths from a few feet to more than 40 feet – think crankbait, without the depth limitations. And like just about any jig-fishing technique, it’s especially adept at drawing the big bites.

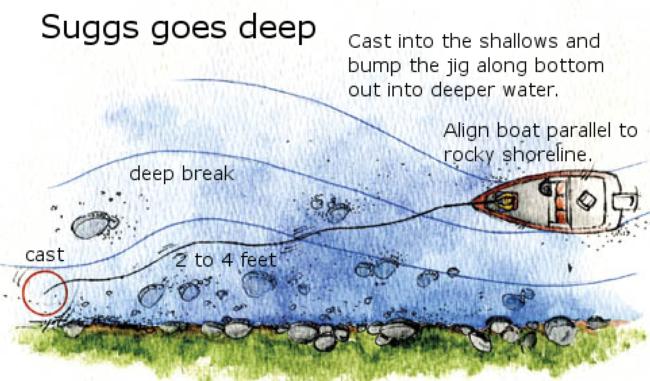

Suggs goes deep

Folgers pro Scott Suggs of Bryant, Ark., has been slow-rolling jigs on Lake Ouachita and Table Rock for years. In fact, it has become a major weapon in his arsenal, no matter where he’s fishing on the Walmart FLW Tour trail.

Whether it’s in shallow or deep water, Suggs believes the presentation’s success is in its ability to draw the reactive strike, which takes a bit of strategy to achieve.

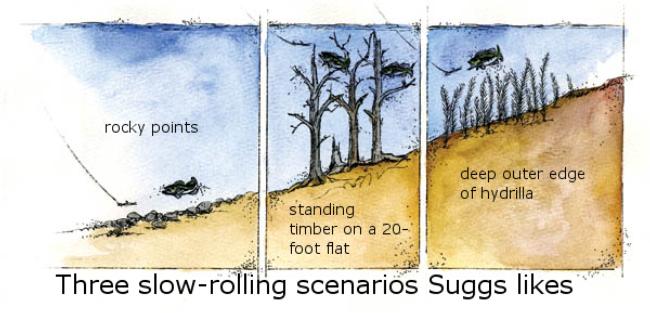

“Whether I’m fishing it shallow and over the top of grass, on the outside edge of a deep grass bed, through standing timber or along a rocky bottom, the key is staying in contact with the cover as the jig swims along,” Suggs says.

The cover contact creates erratic movement with the jig, plus it creates fish-attracting commotion.

Around grass beds, Suggs matches his jig weight and retrieve speed so that the jig swims just through the upper reaches of the vegetation, no matter the depth he’s fishing. He makes a cast, counts it down to the grass and begins the retrieve, snapping free of any grass that “grabs” the jig.

One of Suggs’ favorite patterns, however, is to target bass suspended along the outside edges of hydrilla beds in the 12- to 25-foot range. He casts the jig up to the top of the grass bed, usually about 15 feet below the surface, and slow-rolls it along the top of the grass until it reaches the break, where bass eagerly wait to pounce on his lure. Contact with the cover the entire way ensures his jig breaks the edge of the grass bed at the right depth. When he loses contact with the grass, he tries to maintain the same rhythm and keep that lure coming off the grass at the same depth. He’ll do that four or five times, and if he doesn’t get a bite, he’ll let the jig drop after it breaks the grass to see if fish are holding slightly below that level.

Of course, it’s not always a matter of targeting vegetation. In the deep, clear lakes near Suggs’

Arkansas home, he targets traditional drop-offs, points, humps and other rocky structures in the 25- to 45-foot range. The trick is to fish it almost like a crankbait, where contact with key pieces of cover creates the reaction strike. A lone stump, a patch of gravel or a cluster of boulders are all great targets.

“I rely on this pattern in fall and winter, when the crayfish are most active,” Suggs says. “This technique is one of the few that maintains contact with the bottom throughout the retrieve. Also, it allows you to cover deep water relatively fast.”

The right jig

When slow-rolling around shallow cover, the trick is to pick a jig that won’t drop down too deep into the cover, but that can still make light contact with it. For Suggs, that’s usually a 1/4- to 3/8-ounce model. He steps up to a 5/8-ounce Oldham’s swimming jig for the 12- to 25-foot range. And between 25 and 45 feet deep, he goes with a 3/4- to 1-ounce football-head model.

Once a jig of the right size is selected, Suggs makes an important modification.

“I am trying to give my presentation as much action as possible,” Suggs says. “So I cut the jig’s skirt length so that it’s even with the bend of the hook, and I thin out the skirt material. Those changes allow more water to pass through the skirt. The improved water flow gives the skirt more life and imparts more action to the trailer.”

His trailer of choice is a crayfish-colored Berkley PowerBait Crazy Legs Chigger Craw or the Zoom Fat Albert Twin Tail grub.

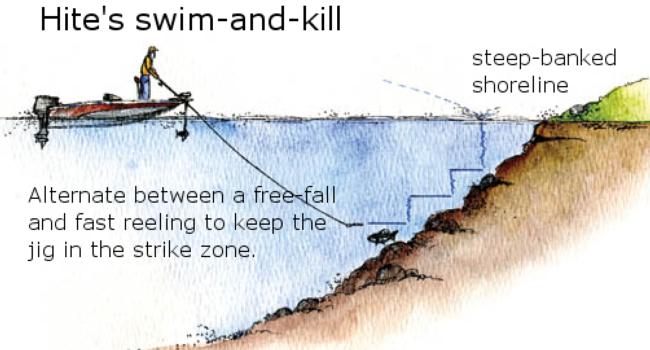

Hite’s swim-and-kill

National Guard pro Brett Hite of Phoenix learned how to swim a jig while fishing his home lakes, San Carlos and Roosevelt. He uses the technique to cover water and draw strikes from keeper-sized fish relating to deep points and flats. While he uses the reel to swim the jig, his technique differs from Suggs’ in that he kills the lure to instigate strikes.

He starts by casting the lure out and letting it fall to the bottom. Then, he cranks the reel handle three to four times before letting the lure fall back to the bottom on a tight line. If nothing bites, he cranks the reel another two to four rotations before killing it again.

“I use this technique when creeping or hopping a jig won’t draw the reaction bite I want,” Hite says.

Hite believes this presentation is imitating both crayfish and baitfish. Crayfish kick off the bottom to escape predators and then drop back down, and then kick again. Likewise, he believes the swim-and-kill action accurately imitates injured bluegill or shad, struggling to escape a predator. Whether it be crayfish or baitfish, the presentation often proves effective when the big bite is tough.

“There are times when you can drag a jig along the bottom and can’t draw a reaction,” Hite says. “This presentation is more erratic than dragging or hopping a jig along the bottom, and so it is better at garnering a reaction strike.”

The right jig

Depending on the depth he’s fishing, Hite uses either a 3/8- or 3/4-ounce football-head jig with a weedguard. He chooses a trailer with lots of kicking action, such as a 5- or 6-inch Yamamoto Double Tail Hula Grub. When the bite is tough, he’ll also switch to a 3 3/4-inch Yamamoto Flappin’ Hawg, which has “wings” that help it glide when falling on a tight line.

When it comes to color selection, Hite keeps it simple. His favorite jig and trailer color combinations are either a shad- or crayfish-imitating color. More times than not, he uses a translucent white with blue, silver and chartreuse flake, or a green pumpkin or watermelon trailer.

Advanced lessons

Reel needs

Hite and Suggs agree that you don’t slow-roll a jig with the rod; it’s done with the reel. Whether in 2 feet of water or in 35 feet, the key is matching the speed at which the reel handle is turned to the water depth being fished – faster for shallower water, slower for deeper water.

Because the reel is such an important part of the technique, choose the retrieve ratio carefully. Hite prefers an Abu Garcia Revo Premier with either a 6.4:1 or 7.1:1 gear ratio, because it allows him to pick up line fast and catch up with a bass moving toward the boat. Suggs also likes the Revo Premier 6.4:1, however, when fishing as deep as 35 feet, he picks up the slower Revo Winch with a 5.4:1 gear ratio.

“That 5.4:1 ratio allows me to turn the handle at a comfortable speed, and because of the gear ratio, I’m not turning it too fast to keep the bait down near the bottom,” Suggs says.

The pros prefer 15-pound-test fluorocarbon line. Suggs switches to 12-pound-test when fishing between 35- and 45-foot depths, because the water resistance created by the larger diameter line prevents him from getting his lure down deep enough. Fluorocarbon lines have very little stretch and allow for better hooksets with the deep jig.

Rod angles

While the pros agree on how to slow-roll the jig, they differ somewhat in how they hold the rod.

“A lot of anglers point the rod down at the water and the lure, but I’m strict about keeping my rod at a 45-degree [upward] angle,” Suggs says. “I like that position because when the jig does make contact with the grass or cover, I only need to make a 6-inch pop with the rod and the jig will pass right on over it. When the rod is pointed down and you make contact with the grass, you have to jerk the rod sideways to clear the grass. If a bass comes up and hits it as the jig tears free of the grass, your rod is in a bad position for a good hookset.”

Hite’s opinion on the matter differs. Unlike Suggs, Hite keeps his rod tip down and aimed at the jig while cranking the reel.

“Sometimes, you’ll begin reeling and the rod will load up because the fish has the jig,” Hite says. “You don’t want a rod that’s really stiff because you’ll end up ripping the lure out of the fish’s mouth. You want a rod that will load up a little bit on the tip. After that rod begins to load up, I reel fast to collect slack and use a side-sweep hookset.”

Where and when

As explained, slow-rolling a jig works from the shoreline shallows to the depths. But is the technique limited to a specific time of year or over specific cover or structure? Not according to Suggs.

“This technique will work anywhere you go in the country because there are so many applications for it,” he says. “You can fish it over the top of eelgrass on Lake Okeechobee, or over the outside edge of a deep hydrilla bed on Sam Rayburn. And there’s no better technique when targeting bass suspended in deep, standing timber than swimming a jig. The only two things you need to know to be successful are what forage you’re imitating and at what depth the fish are in.”

“A swimming jig is a very valuable tool when the bass are in a postspawn pattern and relating to structure like points and flats, or suspended off the edges of channel breaks,” Hite says. “You can also use the technique to catch late staging fish on secondary points.”