Stacked like smallmouths

Fall smallmouth movements in rivers and small reservoirs

————————————–

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the October 2006 Bass Edition issue of FLW Outdoors Magazine. Learn more about FLW Outdoors Magazine and how to subscribe by clicking here.

————————————–

We used to say “stacked like cordwood” when walleyes were tightly grouped. But now that we know how smallmouths behave in late fall, “stacked like smallmouths” is an even better analogy. Bronzebacks pile into dense schools come autumn.

In summer, smallmouth bass commonly spread throughout miles of small, shallow rivers – a few here, a few there. The water’s low, fairly warm, and shallow rocks and boulders create riffles where the water’s well oxygenated and the surface is disturbed, forming overhead cover. Rocks break the current, forming places for smallies to wait just out of the flow in perfect position to ambush food items that haplessly drift by. Water barely deep enough to cover their backs can hold smallmouths, although given their druthers, 3, 4 or 5 feet of depth is preferred over skinnier flats.

But then fall approaches and everything changes. Funny what a difference a few degrees makes. Once smallmouths sense the environment beginning to cool, events are set in motion. Instinct tells smallmouths to begin moving. Some move upstream, depending on the locale. Many more, perhaps, move downstream and for good reason.

Smallmouths in lakes, rivers and reservoirs all begin seeking the stability and safety of deeper water when fall begins to set in. River fish, in particular, take this rule seriously. They don’t have room to make mistakes. River sections that largely dry up during low water conditions can leave them stranded in shrinking pools. That’s a mistake they can’t afford to make even once. When nature calls, it’s time to pick up and seriously head for deeper water.

In most cases, the safest bet is to move downstream. Downcurrent suggests deeper pools. Downstream leads to the deeper water above dams, even if the lakes they form are relatively small and shallow. They’re still deeper than shallow river stretches. Think about it. Anywhere there’s a dam, the deepest water in the area lies immediately upstream. That’s where the fish from miles and miles upriver are heading – the Mecca of river smallmouth locations in fall.

It’s like Mother Nature pulls a plug and all the bass begin swirling downcurrent, inexorably drawn down the drain.

In early fall, with water temperatures in the mid-50s, you’ll notice the shallowest riffle sections suddenly becoming devoid of fish or at best holding passing groups of smallies for brief periods. The dependable bounty of summer boulder flats and shallow current breaks is over. In fact, location patterns begin to break down. The pattern is that the fish are moving, taking up only temporary residence on their way to a distant winter wonderland.

Rather than stopping to fish distinct types of spots, the best bet is to begin covering water – miles of it. Cast to fallen trees in the water if the river’s high enough to have flooded shoreline cover. Hit some rock points. Sweep your lures against deeper outside bends with deeper holes and up into shallow current breaks formed at inside bends. Fish ahead of and behind islands, across weedy bay mouths and into logjams. Absolutely anything, anywhere, is fair game – but preferably with deeper water close by.

Early fall is time for crankbaits, with a nod to spinnerbaits if the river’s high enough to offer flooded wood cover. Otherwise, tie on a crank and go. Something bassy that dives maybe 5 to 10 feet deep, like a Rapala DT-6 or DT-10, Storm Big Bass 10 or Wiggle Wart. Play with color patterns: crawfish, bluegill, shiner and shad. Most importantly, just cast, cast, cast your way downstream, hitting anything that looks fishy – rocks, holes, whatever.

Eventually, it pays off. You will find a cluster of fish and catch a few within a limited area. They may not be there tomorrow – probably won’t be, in fact. But your paths crossed, and you intercepted them. Then you start moving again, repeating the process but now on the lookout for conditions that resemble the area where you caught bass.

Water temperatures in the low 50s and high 40s can be hit and miss as waves of smallies pass through river sections in short order. But as the water dips toward the mid-40s, the results begin to take hold. All those moving fish have to be going somewhere, and there are even more following closely behind, soon to arrive … somewhere. Where can that be?

The answer may simply lie in fish moving miles to gather in deeper holes formed at river bends, the junctions of feeder rivers with the main flow, bridges, or any natural or manmade formations that deflect enough current to form holes.

More likely, however, is that after miles of movement – be it a few miles, dozens of miles or even more – the fish are finally going to reach the top end of a reservoir, and the water is going to start becoming noticeably deeper, wider and with less current. This is the kind of place where it’s safer and easier to spend the winter, out of the current, without worrying about running out of food and, uh, water.

This is the gateway to smallmouth Mecca. Now that you found the doorway, step through it and check out the territory.

In a larger, deeper reservoir with sufficient depths and a lack of current, those first few miles of upper lake are likely to hold some pretty good bass during fall and perhaps through the winter. The fish have everything they need to survive, and they don’t have to fight current when the water gets really cold. Smallies don’t play that game. They move to areas with extremely slow to almost imperceptible flow, although they typically remain in or very near deep enough water, meaning 10 to 20 feet and sometimes more. Look for them on the downstream sides of points jutting into the lake – especially if there’s some rock or wood cover – or the deep outside bends of the river channel, with a few branches and logs washed into the hole.

Now, consider the options for bass that reach the top end of a lake and find it widening and the current slowing – but the water remaining uncomfortably shallow. Logically, they don’t have the luxury of stopping and must keep on moving down-current in search of deeper, slower, virtually slack water with some form of suitable deeper habitat to spend the winter.

When you’re dealing with small, shallow impoundments that are eight, 10 or 12 miles long but only max out at 15 to 20 feet deep, it’s not unusual for smallmouths to move down through the length of the reservoir and take up winter residence in the extreme lower end. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll hug the upstream boulder face of the dam all winter – although they could. But any suitable structural conditions in the last few miles of lake have to be considered fair game for the mother lode.

So you begin checking the options, driving around and watching your electronics for the presence of fish – both big fish and baitfish. Check in outside bends where the channel sweeps against steep banks, perhaps with some fallen or standing trees, or where the channel swings away from shore, forming shallow sand or possibly even weed points that drop precipitously into the channel. Midlake humps (even if they subtly rise only a foot or two off bottom, more a product of a change in bottom composition than a major structure, and deeper holes in the middle of nowhere – the kind you stumble upon when crossing the basin at high speed and happen to be watching your depth finder) – can all hold fish.

Somewhere in this vicinity of the lower lake there are places, likely more than one, where the combination of depth, bottom content, slow flow to slack water, forage concentration and cover all come together to form the promised land. The kind of place where, if you drop an underwater camera, the bottom is going to be paved with smallmouth bass – big ones. The compressed adult population of many river miles all drained down into a holding area that, in reality, isn’t all that big. And the scary thing is, as time goes on, it’s only going to get more crowded as wave after wave of new smallmouths enter the area and begin wedging between the others until they’re, well, stacked like smallmouths in fall.

The same type of massive fall concentrations occur in lakes, reservoirs and on the Great Lakes as fish from wide areas assemble in key spots, generally at the base of a drop-off somewhere along a key main-lake structural element, somewhere in the 30- to 50-foot range – different habitats but the same principle. When you find them and figure out how to catch them, it’s lights out. The size and numbers are bewildering.

So much so, in fact, that several years ago the state of Minnesota decided to close the smallmouth season after early September, prior to the fall bunch-up. They recognized how vulnerable a huge smallmouth population could be to anglers who irresponsibly overharvested these intensely concentrated and vulnerable fish. You can still catch them, but you have to release them. The best of all worlds.

Cold-water tactics

When bass are stacked up, there are several key ways to catch them. While most tend to work best within certain water temperature ranges, these are only guidelines. It’s best to approach the situation with an open mind, prepared to experiment with a variety of key techniques to see what works best under the conditions.

In early fall, with water temperatures in the mid-50s to high 40s, use crankbaits and spinnerbaits and do lots of casting and moving to cover water and intercept moving groups of bass. Try trolling mid-depth holes with crankbaits that dive to and scrabble along near bottom, moving just fast enough to wiggle the lure. Troll steep shorelines in lower reservoir sections where the current is negligible where bass are beginning to arrive in wintering holes. The fish are still quite responsive to quickly moving lures at these temperatures.

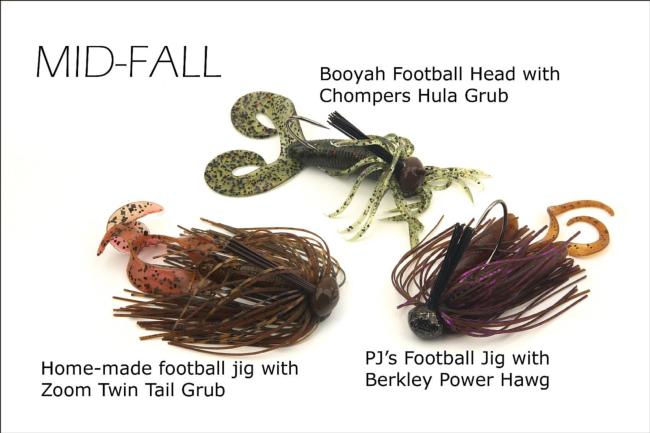

By mid fall, with water temperatures entering the mid-40s, these tactics will likely still produce to some degree. Yet you’ll begin to notice a shift toward classic fall tactics, particularly as more bass begin settling into winter locales. Now, you want your presentations to be more bottom-oriented and noticeably slower. Rather than quick retrieves or trolling passes, slow things down to a crawl.

This is time to scratch a jig-and-pig (where there’s scattered wood cover) or a 1/2-ounce football head and spider grub (around rocks and gravel) across the bottom. Cast out, let the lure fall to bottom, and either lift the rod tip to dig-dig-dig it across the bottom or simply point the rod tip down and reel slowly enough to feel the jig scrambling across gravel. Don’t hop it. Don’t pop it. Creepy crawling is best.

If you prefer a more vertical tactic, more like classic North Country walleye and smallmouth fishing, try vertically jigging a jig and minnow combo, or backtrolling a live-bait rig baited with a 4- to 6-inch chub or shiner. Smallies seem to respond to bigger minnows better than smaller ones at this time of year. When a big, lively minnow creeps past their noses, starts panicking and wiggling and trying to escape, bass can’t stand it.

Smallies seem to grab big minnows by the tail a good part of the time, so give them a little time to reposition the minnow and get it down far enough into their mouth before setting the hook. If, however, the fish hits and runs off like a freight train, that indicates there are more buddies around trying to steal the minnow. Good sign! You might have to set the hook right away before the fish takes too much slack and then hope for the best.

By later fall, with water temps below about 43 degrees, even more bass should be gathering in prime areas, but they’ll begin getting fussier. Jigs and minnows or live-bait rigs are still good candidates, although you’ll begin noticing lighter bites, with the fish often holding the bait by the tail, and many missed strikes. This is especially true with live-bait rigs and big minnows. Surprisingly, switching to smaller minnows may get no response at all! When you feel a light bite, with the line barely getting heavy, lift the rod tip slightly to put a hint of pressure on the fish then back off. This often forces them to take the minnow in deeper, since it seems like it’s trying to get away. Sometimes it works. Sometimes they drop the bait. It’s all part of the game, but teasing them sometimes helps.

You’d think the minnow thing would be the last hurrah, remaining productive longer than anything else. But not necessarily. Because smallmouths tend to hold and drop baits a lot when the water gets really cold, consider a possible transition to super-subtle tactics like a hair jig barely held above bottom or a marabou jig breathing before their noses – something subtle and virtually stationary that they can study for awhile and then plop fully into their mouths without much effort.

A drop-shot rig with a tiny 3- to 4-inch subtle worm is another option at this time. Just don’t overwork it. Position the bait a foot or so off bottom. Once again, use minimal movement and let the bait sit there before their eyes. Drift or creep along with your trolling motor, pausing where you see fish on your electronics. Try to hold it as still as possible, which means it’ll still have slight movements – just enough to look alive.

Ever so slowly move through the fish, your line vertical below you, with your lures barely scratching bottom or held just above. You must use minimal movements – teasing and tempting, rather than triggering. With a whole herd of fish down there beneath you, even if only a small percentage of bass respond, you’re going to have a good day.

That’s the wintering-hole phenomenon. Early in the game, it’s fish after fish on just about anything you put in the water. But little by little, their mood shifts, and you must react to keep catching them in abundance. All the lure styles mentioned here have a time and place in your fall smallmouth repertoire. Bring them along, have a selection rigged up on several rods, and be prepared to try different approaches to see what works best.

By the time the water temperature drops below 40, those fish are going to get mighty touchy. Calm, clear, warm afternoons are best, with bass showing brief flurries of activity. Cold front conditions are not good times to hit the water. Bass are still there, mind you. Just drop your camera for a look-see. It’s still awe-inspiring, no matter how many times you see it. Potentially hundreds of big bass, stacked like smallmouths, heading into winter repose.