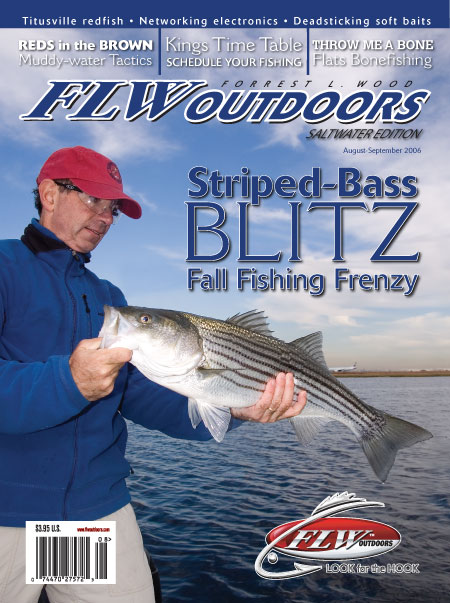

The fabled fall striper run

As the water gets cold along the East Coast, striped bass are on the move

It was like a scene out of Hitchcock’s “The Birds” as we rounded the corner and approached the inlet. “Hold on!” I screamed over the delightful hum of the four-stroke outboard as I pinned the throttle and headed for the immense clouds of wheeling and diving birds. Two hats flew off and went careening into the rooster tail behind the boat, but there was no turning around to get them. There was a fall striped-bass blitz of epic proportions forming against a threatening gunmetal-gray sky in front of us. We approached with a sense of utmost urgency.

As we got closer, white splashes could be seen, and even before I could get to the mayhem just off the jetty, shiny juvenile Atlantic menhaden jettisoned out of the water all around the boat under heavy boils in desperate but futile attempts to flee hungry predators, only to be picked off from above by opportunistic gulls. Before I could even cut the engine, my two anglers were zipping topwater plugs into the boiling fish.

“I’m on!” screamed one, as a big striper’s head shook and splashed on the surface. Behind me, I could hear the zing of line peeling against the second angler’s drag. The fall striped-bass run had officially begun.

For many northeast and mid-Atlantic anglers, fall is a time of the year when sleep suddenly doesn’t seem that important. We cash in those sick days, chores get neglected, and we make up pathetically transparent excuses to get out of prior commitments and responsibilities. This is the time of the year we lust after – when it all comes together in the form of huge bait concentrations and migrating predators.

Migrating stripers and abundant bait

When these two things mix, the result can be a feeding frenzy of huge proportions. Locals call these phenomena “bass blitzes” or “bass boils.” When the water gets cold, stripers will begin to feel the urge to feed. This evolutionary trait has allowed the species to fatten up and take on plenty of reserve fuel for what is often a very long journey. The American Littoral Society, which has been running the world’s largest volunteer fish-tag-and-release program for close to a decade, has plenty of data showing the vast distances these fish travel. Stripers from as far north as Maine (particularly the large ones) will travel all the way down to the coast of North Carolina where they winter in the Outer Banks region.

When these two things mix, the result can be a feeding frenzy of huge proportions. Locals call these phenomena “bass blitzes” or “bass boils.” When the water gets cold, stripers will begin to feel the urge to feed. This evolutionary trait has allowed the species to fatten up and take on plenty of reserve fuel for what is often a very long journey. The American Littoral Society, which has been running the world’s largest volunteer fish-tag-and-release program for close to a decade, has plenty of data showing the vast distances these fish travel. Stripers from as far north as Maine (particularly the large ones) will travel all the way down to the coast of North Carolina where they winter in the Outer Banks region.

While the larger fish winter over in the Carolinas, there are documented groups of fish that winter over in deep-water holes of the Hudson River. Other groups of fish will travel to the Chesapeake and winter over there. And still, there are resident fish that will stay in deep holes in various estuaries. For the most part, these fish are dormant for the entire winter season, so they too are ravenous during the fall as they need to pack on the fat that will get them through a winter of eating very little.

From north to south

With the ending of August and the beginning of September, the first stirrings of the fall striped-bass run develop in Maine. According to expert Maine light-tackle and saltwater fly-fishing guide, Captain Doug Jowett, mackerel are what fuel this first fall jolt of fish. After that first cold front moves though the region, stripers and Atlantic mackerel clash, and the feed is on. In addition to mackerel, Jowett said stripers begin to aggressively feed on Maine’s lobster population. Harbor pollock are abundant as well as various crab and shrimp hatches. Basically, once the air and water in Maine cool, anything is fair game for the state’s stripers, but the mackerel inspire the blitzes.

From Maine, things spread south to Cape Cod fairly quickly. Jowett follows the action down there to take advantage of some of the best blitz fishing the East Coast has to offer. The ocean side of the Cape is known for its abundant sand-eel populations, while the Cape Cod Bay side harbors massive schools of juvenile Atlantic menhaden. There also seems to be good numbers of Atlantic silverside for stripers to feed on during the September run in the cape.

Toward the middle and later part of September, the fall action quickly spreads south to Rhode Island and Connecticut. New-of-the-year Atlantic menhaden (locally called peanut bunker) fuel the blitz action in these regions. These small to medium baits flood out of the creeks and small bays, and, in most cases, this occurrence just happens to coincide with the annual striped-bass migration. Schools of small pre-peanut bunker that venture out to the inlets on the outgoing tides early in the season will often get bombarded by false albacore and bonito. But once October comes around and the air gets cool, bigger peanut bunker, in the 3- to 4-inch range, begin to migrate out of the bays in large numbers.

Menhaden swim in large schools close to the water’s surface and are easy to spot. They are very distinguishable by their tendency to create small splashes on the surface with their tails and the bright flashing reflection they create as they turn on their sides. Individuals swim in close schools, some of which number in the thousands. When the water gets to be in the 60- to 50-degree range, the stripers turn on like a halogen light bulb. Intercepting large schools of juvenile menhaden, they create mind-blowing blitzes.

Peanut bunker are forage fish to a number of predators, but from North Carolina to Rhode Island, they are arguably the favorite food of striped bass. Their oily, fatty tissue is dense with the fuel that a big bass needs to complete its migration. For this reason, stripers will become intensely voracious when this particular bait is around.

Peanut bunker are forage fish to a number of predators, but from North Carolina to Rhode Island, they are arguably the favorite food of striped bass. Their oily, fatty tissue is dense with the fuel that a big bass needs to complete its migration. For this reason, stripers will become intensely voracious when this particular bait is around.

The entire coast of Long Island, N.Y., as well as Long Island Sound, share in this juvenile menhaden rush. In addition to that, the area gets massive concentrations of bay anchovies, particularly at Montauk Point. Montauk is the eastern end of Long Island, where the Sound and Atlantic Ocean currents meet in a confluence of warm and cold currents. It is referred to by seasoned saltwater anglers as the Mecca of striped-bass fishing. Because of the abundance of bait, striped-bass blitzes form here in ways they cease to form anywhere else in the world. Dense copper-red shoals of bay anchovies dot the region’s waters, and at any point in time massive schools of striped bass erupt in enormous feeding frenzies underneath them. Bay Anchovies range in size from 1 to 4 inches, but the sheer number of them when they school are what makes them so unique. When striped bass encounter them, they attack in schools so thick that they literally appear to be slithering over one another. Usually this happens right up against the beach as schools of marauding bass push the bait toward the shore, allowing them no exit.

Montauk Point is perhaps one of the most extraordinary places in the world during the fall striped-bass run. Catch it on the right day and it’s like something you’d see on the Discovery Channel. Sometimes, it’s enough to just put your rod down and watch the mayhem unfold as these fish go to town on bay anchovies. It can be truly spectacular. The best time to witness and fish this phenomenon is from mid-September to mid-October. Be warned however – Montauk’s wonderful fishing is no secret, and it is one of the most crowded and competitive spots in the world. Add the often unpredictable weather conditions, long period ocean swells and extremely strong currents and things can get dangerous if folks act stupid. Every year at least one boat ends up on the rocks.

The rest of New York’s coast enjoys the peanut bunker and bay anchovy phenomenon, but not to the same extent as Montauk. Still, the fishing can be good, and the area does get its fair share of bass blitzes. Surprisingly, some of the best fishing in New York exists in Lower New York Harbor and in Raritan and Jamaica bays.

New York and New Jersey coasts also get a finger-mullet run. White mullet show up in mid- to late August and stick around for a month or so before moving back to warmer waters. This long and slender baitfish usually ranges in size from 5 to 8 inches, is bluish-gray on its upper body and fades to silver on the sides and white underneath. They ingest food by picking up sand from the bottom and sifting edible material through gill-rakers and tiny teeth. The rough, washed sandbars in late September and early October offer dislodged food in the form of tiny crustaceans, bringing in mullet in large numbers to feed.

The flesh of this species has one of the highest sources of omega three fatty acids, making it a sought after food source for hungry stripers. When you find the mullet schools, you’re sure to find hungry predators in close proximity. When the surf is particularly big, those mullet that have gathered to feed amidst the suspended sand are also very susceptible to getting tossed around by the roiling water. Disoriented mullet often get separated from the school and can be seen bouncing out of the water with a big striper or bluefish in pursuit. On a clear, sunny day, one can observe this spectacular occurrence with some clarity. Seeing roving schools of large bluefish and stripers inside a swell as it rolls in is a regular occurrence during this scenario, and the presence of mullet, because of their oil content and size, usually seems to bring in the largest of predators to feed.

Because the water temperature is still a bit warm in this area for daytime striper fishing, you’ll have to be out there at the crack of dawn. In October, as the water cools, midday striper fishing can become more productive. Overcast days and big surf usually means the striper action on the mullet will be good all day. Surfcasters in New York and New Jersey do quite well when the mullet are around as bass often chase them right in the wash.

Because the water temperature is still a bit warm in this area for daytime striper fishing, you’ll have to be out there at the crack of dawn. In October, as the water cools, midday striper fishing can become more productive. Overcast days and big surf usually means the striper action on the mullet will be good all day. Surfcasters in New York and New Jersey do quite well when the mullet are around as bass often chase them right in the wash.

Late fall in New York and New Jersey can be perhaps the best time to fish this region. November can result in exceptionally good bass blitzes on peanut bunker and bay anchovies. But, in the later part of November and into December, these states typically get a good run of Atlantic herring. Unfortunately, this is usually when the weather seems to be at its worst. Cold weather and strong east winds can often keep anglers off the water for weeks on end. It can also prematurely push the fish farther south. However, if the late-fall season is a warm one and the wind cooperates, these runs of Atlantic Herring coincide nicely with the striped-bass migration.

Because these baits are quite large, sometimes up to 12 inches, the predators eating them tend to be large as well. I remember with great clarity an unseasonably warm mid-December morning when I ended up right smack in the middle of hundreds of 30-plus-pound stripers off New York Harbor chasing herring on the surface.

Southern New Jersey and Delaware enjoy a late-season fall run as well, and it’s a lot more consistent. These fish seem to be on migrating Atlantic menhaden in November as well as some herring in December. Virginia enjoys good blitz action in November as well, but doesn’t really peak until December. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel has become known world-wide as a world-class striped-bass fishery in December. These fish are feeding mostly on juvenile Atlantic menhaden schools and can be spotted along the coast and in the mouth of the Bay just about anywhere at any time.

The bulk of the stripers ultimately end up in the Outer Banks region of North Carolina. This area’s blitz season really peaks in January and the bait is overwhelmingly menhaden. This fishery is marked by diving gannets – a large prehistoric-looking bird that wheels over fish making plunging dives into bait schools and blitzing fish. This makes the striped-bass schools easy to find and easy to fish. Again, however, weather can be an issue here. Despite its southern origin, it can still get darn cold. Coupled with the wind exposure to the Outer Banks’ barren islands and you could spend weeks there without getting a fishable day.

Fishing the bass blitz

Let’s face it – you don’t have to be a brain surgeon or even a particularly good angler to fish a bass blitz. Usually, these fish are so fired up that just about anything you throw into the mayhem will result in an immediate hookup. But, there are times when stripers will get exceptionally finicky, even during a fall bass blitz. In these situations, do your best to “match the hatch” in both size and color of your offering as well as the speed of your retrieve. That may not work in some situations due to the sheer amount of bait. If that is the case, I always go bigger and louder. A chartreuse or lime 9-inch Slug-Go is always a good bait, as well as any floating/rattling popper. Nine times out of 10, I’ll start fishing a blitz with a rattling popper as they seem to draw the most explosive and visually appealing strikes.

If you’re catching only smaller stripers on the surface, you may have a shot at larger fish by going deep. You just can’t beat a 3/4- to 1-ounce bucktail jig to do this, especially when the stripers are feeding on Atlantic menhaden. Bass Assassin jerkbaits fished on a 3/4- to ounce jighead are also deadly on those opportunistic big, fat, lazy fish that wait below the feeding school to vacuum up the scraps.

Blitz etiquette

Fall striped-bass blitzes are some of the most awesome displays nature has to offer. And nothing can get your blood pumping like being right in the middle of one of these melees.

Sometimes it can be quite overwhelming, and sometimes folks loose control. Things can get ugly out there and sometimes even dangerous during the fall run. Inadvertently, or purposely, people get cut off and guys zoom into the school, scarring everything away. What starts out as a great and welcome occurrence can quickly become an ugly display of raw greed and anger. However, if folks follow a few simple rules, several boats and surfcasters alike can take advantage of a single, all-out blitz while avoiding line tangles and unkind words.

First, don’t troll through a blitz. There is nothing quite as rude as a boat trolling wire through a school of breaking fish when everybody else is drifting into them while trying hard to be as stealthy as possible. More times than not, trolling through puts the fish down right away. It takes a lot less work, and it’s a lot more fun to cast into these fish with light tackle and feel the hit as you’re reeling.

First, don’t troll through a blitz. There is nothing quite as rude as a boat trolling wire through a school of breaking fish when everybody else is drifting into them while trying hard to be as stealthy as possible. More times than not, trolling through puts the fish down right away. It takes a lot less work, and it’s a lot more fun to cast into these fish with light tackle and feel the hit as you’re reeling.

Don’t run your boat in the middle of a blitz. Most of the time, it’s going to put the fish down for everyone. With a little boat handling as well as some tide and wind drift recognition, you can increase your odds of pulling more fish out of the pod and at the same time not anger the rest of the crowd fishing the pod. Set yourself up with the wind and tide so that you will drift effortlessly over the pod of fish. This takes a bit of “on the water” knowledge, but with a little experience and practice it can be mastered quickly. More often than not, if you can employ this method correctly, you’ll find yourself smack in the middle of a blitz.

When employing this method of letting the wind and tide push you quietly into the school, it’s important for your own success, as well as those around you, to turn your motor off. Yes, sometimes the fish are so lit up that they will continue feeding when you leave the motor on, but it will often spook them. The urge to leave it running is brought on by that “run and gun” immediacy of being able to zip over to where the school pops up next. But, if you leave the motor off, you won’t have to pick up and run all the time.

Don’t restrict yourself to just the blitz. Just because the mayhem has settled down doesn’t mean you have to pick up and run over to the next school. Odds are pretty good that there are still fish where that pod of breaking fish once was. If you can calm down enough to take a look at your fish finder, you’ll see that this is true. I’ve generally caught my bigger fish in the blitzing scenario fishing in the lull of the blitz. The big, lazy fish will hang out and suck up all the dead or stunned baitfish. So when the mayhem has died down, hang out for 5 or 10 minutes and fish a jig or sinking line if you’re a fly-angler.

The last, and probably the most important rule of basic blitz etiquette, is don’t get anywhere near the guys fishing from the beach or jetty. At times it’s almost irresistible to motor up into shallow water and toss in a few casts to ravenous busting fish, but be very conscious of those working the beach. You have the whole ocean to fish. Those guys only have the beach or the jetty to fish. Give them their space and when a blitz comes close to the beach, let them take advantage of it. If you decide not to, you might find yourself showered with 3-ounce diamond jigs. Not fun! In addition, if you get out of control and just can’t help going into that surf line, you could very likely find yourself on the face of a rather large wave and, subsequently, underwater as your boat gets tossed on the rocks.

Fall striper blitzes are what every fisherman dreams of. I love them, and while catching fish is great, just watching the mayhem is sometimes enough for me. Being there when nature’s predator and prey relationship shows itself in such a lucid and violent display is just cool.