Break out

Sometimes you need to stray from obvious sources of cover and hit the breaks

A lot of people believe late spring and summer fishing desert reservoirs is all about spots, but it really isn’t. While there are parts of some of these lakes – such as Lake Mead – where bigger bass are often caught – some of those areas are not always available due to low water levels.

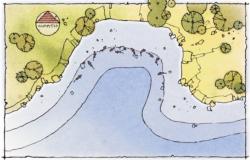

This is when we see the most productive areas are the available cover and types of breaks that are present in and around spawning areas. Anyone who has driven to Lake Mead or flown over any of the lakes along the Colorado River has seen there just isn’t much shoreline cover on these clear reservoirs.

When there is some cover, not only do the fish use it, so does every angler who comes into the area. In a multiday tournament, by the time the practice days are over, every obvious spot in the popular bays has been hit. That’s why anglers have to look past the most visible cover and pay more attention to breaks.

As a side note, while I focus much of my efforts and analysis on the lakes of the Southwest, lakes around the country present nearly identical conditions – deep and clear water, minimal shoreline cover and fairly heavy fishing pressure. Just look at the White River lakes, or several of the Tennessee River lakes.

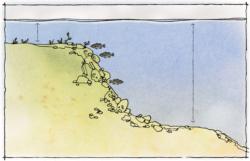

Each desert lake is a little different. Lake Havasu has the most grass, but is rocky in nature. Lake Mohave has some grass, but its scrub wood is the most important cover in the springtime. Lake Mead, especially for the last five or six years, is mostly about rocks. And because of that, the places that hold key fish are the “first breaks” near a spawning flat. The break doesn’t have to be much, maybe only a foot difference in depth. There could be a migration route like a channel depression.

After that, you need to look for some variation on the break like a little rock pile or a lay-down piece of wood. This type of spot on a spot is where the biggest fish in the area is probably going to be.

There is a cycle of daily fish movement during the spring that not everyone notices. In the mornings and again in the afternoons, the fish are a little deeper on the first break or first point with a deeper side that is close to the spawning area. Later in the season when the spawn is on, or later in the day during prespawn or postspawn, the fish will come shallower either to nest or to feed.

What’s interesting is, even after the spawn, the fish will be in the same spots – the first breaks – if there are bluegill or shad in the same areas. What was kind of like a waiting room in the maternity ward during the spawn is now an ambush point for feeding once nesting is over.

But not all key breaks are physical in nature. They don’t have to be rock or wood, there can be a “light break” that does the same thing. Sometimes the light break is caused by some variation in water clarity, as with algae or silt, and sometimes it’s just shadows at a certain time of the day. In every area that you scout, you should make sure you are checking light breaks as closely as those where the bottom changes.

Don’t decide where the bass should spawn and then just scout the areas that lead that way. You always hear the successful anglers talk about the time they spent looking, not just the time they spent casting and fishing to find their best areas. Many times in desert lakes, fish don’t spawn in the backs of pockets, because there just isn’t enough cover there to suit the adults or protect fry.

Don’t decide where the bass should spawn and then just scout the areas that lead that way. You always hear the successful anglers talk about the time they spent looking, not just the time they spent casting and fishing to find their best areas. Many times in desert lakes, fish don’t spawn in the backs of pockets, because there just isn’t enough cover there to suit the adults or protect fry.

That’s why the fish like to spawn on flats. Key places have some deep water or deep channels that lead them up to these flats. There isn’t much going into the back of the coves. Now, if we had high water, there would be brush lines, and then you would find fish right at the base of the brush.

But what is most noticeable at Lake Mead is that almost every bed you find has some kind of stick in it. As barren as much of the lake is, in the spring, if you look closely, you will find a stick.

These sticks don’t show up until the bass have fanned their nests; that’s why it is such a key thing to look for. It may be something an inch in diameter and a foot long, but it will be there in the nesting area. When I see one of these sticks during the spring, even if I don’t see a fish anywhere, I always cast to it. The fish can show up out of nowhere.

Although this article is about fishing breaks, remember, they are linked to spawning areas. That means you may locate fish by working from the breaks to the spawning flats, or you may go the other way and work out from the spawning areas.

If there are a few areas that still have a little bit of grass around, which is always good for holding a few little bluegill, bass are usually nearby.

A last point to make about the better spawning areas – both high-water and low-water cycles – is that the best coves are the ones that are protected from any north wind or any kind of seasonal storm front. Even in a climate where the air temperature can jump up to 80 degrees during March or April, with the cold desert nights, it takes longer for the water to warm up. Protected water may be only slightly warmer, but it’s usually enough to make a difference.

With more and more fishing pressure and more and more anglers understanding which breaks and ledges hold bass, it takes a more careful approach to get bit – especially by bigger fish. The clear water on many reservoirs makes fish more wary about your approach, so it is important to be quiet when fishing and make long, accurate casts.

The key to the best presentations is to get yourself lined up and put the bait exactly where you want it. For fishing rock piles, go with a football-head jig as your No. 1 big-bass bait. Normally, a brown-skirted jig with a purple No. 11 pork frog works well. Go with a 3/8-ounce jig early in the year and later go to a 1/2 ounce. Mix in a spider jig of the same weight in green pumpkin to cover your bases. Deep-diving crankbaits are also a staple in many lakes.

Drop-shotting using 6-pound Vanish line and a 3/16-ounce Mojo sinker is another productive technique. This elongated sinker is very good around wood; it comes through easily and doesn’t disturb the area. Often, you don’t want a lot of action with any of these baits; you just want them to quietly appear in the zone, where the dominant fish in the cover has to react.