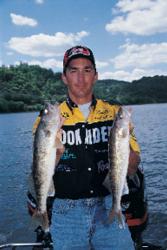

Performance Profile: Keith Eshbaugh

Back to nature

The landmarks were right on the money – a good thing since the directions did not include GPS coordinates. At the end of the rutted trail was a campsite that could pass for something from “Survivor,” except an icy wind and deep snow replaced the tropical breeze and sandy beach enjoyed by the castaways on the hit television series.

This wasn’t the setting for another reality television show. Instead, this was the off-season home away from home for Wal-Mart RCL Walleye Tour competitor Keith Eshbaugh of West Alexander, Pa. Should you ever make it onto “Survivor,” Eshbaugh would certainly be an individual that you would want in your tribe.

Can you carve a bow from a monkey-ball tree with only a broad ax and drawknife, braid a bow string from dogbane, craft arrow shafts from river cane, fletch the shafts with turkey feathers and chip stone arrowheads from flint? Eshbaugh can.

Tournament competitors don’t need to watch reality TV. They get a good dose of reality on the water, whether it’s a competition day, practice day or just a fun day of fishing. Anglers know that fishing is the true reality.

While many pros continue their interest in the outdoors during the tournament off-season by diving into hunting, Eshbaugh takes his enthusiasm for nature to a whole other level.

“Over the years I’ve harvested deer with every type of firearm,” Eshbaugh said. “It became too routine. So I started hunting with a modern compound bow. It was too easy as well. There just wasn’t any challenge left. That’s when I met a craftsman who turned me on to bow-making, thereby allowing me to hunt with an instrument that I made.

“Anyone can stand on the edge of a field and shoot a deer with a high-powered rifle at a considerable distance. But how many are willing to hunt with a homemade bow and arrow that has a 20-yard kill zone?”

It isn’t enough simply for Eshbaugh to hunt with a handcrafted bow. He also lives a primitive lifestyle during his hunts by residing in a tepee.

“This has evolved into a tradition; several friends and I spend a week hunting from my tepee somewhere in Pennsylvania during the muzzle-loader season right after Christmas,” Eshbaugh said. “This isn’t your typical hunting camp with all the amenities; this is definitely roughing it. Temperatures at this time of year are usually around zero, so to survive you have to know what you are doing.

“This has evolved into a tradition; several friends and I spend a week hunting from my tepee somewhere in Pennsylvania during the muzzle-loader season right after Christmas,” Eshbaugh said. “This isn’t your typical hunting camp with all the amenities; this is definitely roughing it. Temperatures at this time of year are usually around zero, so to survive you have to know what you are doing.

“I’ll kill one deer each season with a muzzle-loader just to be sure my family has food in the larder. But any bonus deer I harvest will be taken with a homemade bow and arrow. It’s as close to nature as anyone can get.”

If you encountered this mild-mannered 35-year-old for the first time during tournament season, you would never guess that during the off-season he goes native.

“I have American Indian in my lineage, but that’s not why I do this,” he said. “I’m not in a re-enactment group, nor am I making a political statement. I can’t deny, however, that my Indian heritage plays some role. I have always liked Indian lore and loved to make things with my hands. I’ve grown tired of the easy way to hunt with firearms. Modern gun technology turns me off.”

And the tepee? Eshbaugh was introduced to tepee camping by a friend several years ago. He had so much fun that he acquired his own tepee.

“A tepee is an amazing design,” Eshbaugh said as he eagerly showed off his temporary abode. In the center of the tepee a wood-burning stove maintains an interior temperature of 60 to 80 degrees even in the coldest winter weather. The stove is used in place of a traditional open fire for safety. The smoke is piped to the apex of the poles and out the small opening. The inside skirt liner covers the ground and extends up the walls, attaching to the poles about 3 feet above the ground. This allows rainwater running down any of the 15 poles to drain directly to the ground without pooling on the floor.

“All of this – the primitive weapons and tepee camping – wasn’t part of my childhood,” Eshbaugh said. “It was something I found interesting, exciting and different later in my life. It’s as real as it gets.”

Growing up in western Pennsylvania, Eshbaugh led a fairly routine life. His father introduced him to fishing by taking him and his brother Curt to area trout streams. Angling wasn’t a passion with his father. It was simply one of many activities that he did with his kids. But the fishing bug infected Keith.

“My brother Curt and I sold live bait through high school,” he said. “We made enough money to buy our own fiberglass boat in 1985, the year I graduated high school. It was a 1961 Larsen with a 10-horsepower outboard. We fished from the boat until I started tournament fishing in 1996, at which point I bought my first Lund.”

Purchasing his original boat enabled Eshbaugh and his brother to explore the nearby Allegheny River. He admits they didn’t know what they were doing at first, but it was all part of a learning process.

“It wasn’t until we took the boat to Pymatuning Lake that I caught my first walleyes by trolling,” he said. “That really sparked my interest, and from that point on I never wanted to fish from shore again. Walleye fishing became a passion, and trolling evolved into my preferred method to catch them.”

Eshbaugh began his tournament career fishing local walleye tournaments in Pennsylvania and as an amateur on the old NAWA Circuit. After a successful finish with Joe Puccio in a team event on the Mississippi River, Eshbaugh switched to the pro side. Nowadays he fishes from a Ranger 620 in both RCL and PWT events.

“Shortly after switching to the pro side, I recall thinking, `This is a little harder than I thought it would be,'” Eshbaugh said. “Every competitor enters a national circuit thinking they can be No. 1. But you quickly discover that the top dog position is difficult to obtain. It’s tough to survive on tour with all the talent you are competing against. I cash checks every season but never seem to be positioned to win an event.”

On the home front, Eshbaugh has been married to Natasha for five years. They have two small children, William and Anja. The Eshbaughs recently moved onto a 200-acre farm southwest of Pittsburgh, about an hour from Keith’s favorite fishing holes on the Three Rivers – where the Allegheny and Mon merge to form the Ohio.

“I’m also a hobby farmer,” Eshbaugh said. “We plant soybeans, corn and sorghum for wildlife and grow some vegetables for home use. But the bonus of country living involves the four ponds on the property, stocked with bluegill, bass and catfish. Now when I’m home, I can take the kids fishing any day they want to.”

Natasha understood from the beginning that Keith wanted to pursue a career as a pro angler. “When we first started dating, I traveled to the tournaments with Keith,” she said. “The competitors’ wives would get together to commiserate, with the biggest issue being how much time their husbands spent on the road each season. I didn’t quite understand that at the time. Now I do. As a pro, Keith is away from home at least 10 weeks a year in order to fish the circuits.

“That really hasn’t been a problem, however,” she said. “I have a full-time job, two young kids to care for – fortunately with the help of good child care – and a 15-year-old from a previous marriage. I grew up on a farm, so I know how to fix things if something goes wrong here at home. We all miss Keith when he’s gone, which makes for more enjoyable time when we are all home together.”

High-tech angler vs. primitive hunter

High-tech angler vs. primitive hunter

When not on the road, Eshbaugh maintains an active schedule. He books guide trips to local walleye waters, including the Three Rivers, where he puts clients on walleyes, saugers and hybrid white bass during the late fall and winter. He also works sport shows for his sponsors.

“When I first started fishing tournaments, I didn’t have sponsors or actually understand how to get them,” he said. “I began sending in reports to the companies whose products I used successfully. Eventually, that led to solid sponsorship support. Currently, I am the only full-time professional walleye angler in Pennsylvania – a fact not lost on sponsors who depend on me to help promote their products throughout the state.”

Eshbaugh explains that he does not see any inconsistency between his dedication to primitive hunting and his full-time pursuit of high-tech fishing.

“I don’t need the modern technology to successfully track and harvest a deer because that animal is on land – we are both in the same element. With fishing, however, the target is swimming in an aquatic environment. Therefore, I must rely on technology. In both situations, you must use your brain to figure things out.

“For example, when fishing with sonar, I convert a two-dimensional screen image into a three-dimensional picture in my mind. Then I need to factor in current direction, prey movement and predator intercepts just as I take wind direction and feeding routes of deer into consideration. To my way of thinking, they are closely related even if the mediums are at different ends of the spectrum.”

Eshbaugh does not expect nationwide fame and untold fortune on the tournament trail. He is content to work at improving his position in the circuit standings in order to put together an adequate income along with fees from seminar engagements, guiding and sponsor support. In a profession that sees many newcomers throw in the towel after a season or two, Eshbaugh is a survivor.

Keith Eshbaugh learned the craft of bow-making from craftsman Mike Churney. Eshbaugh has made three bows and has others in various stages of readiness.

First, he starts by locating the right tree. “Osage-orange, also called monkey-ball tree, is my preferred wood,” he said. “You find a lot of them in Pennsylvania because farmers planted them as fencerows. You must find one that has a straight trunk. If it is twisted or has grown around barb wire, then it is worthless for my purpose.”

After cutting the tree down, a 72-inch section of trunk is selected. The balance of the tree is used for firewood. The selected trunk section is split lengthwise and then split into pie-shaped pieces; each section can be crafted into a bow. Eshbaugh removes the bark from one pie section and determines the widest growth ring. Then he pencils in the length and shape of the bow.

“That is where the strength of the bow comes from – the major growth ring. I use a broad ax to take the wood on the front and back down almost to the major growth ring. Then I switch to a drawknife for close work and sandpaper to finish the job. As long as the two ends of the bow are even from the same growth ring, it will shoot straight.”

Using only hand tools – a broad ax, drawknife, rasp and sandpaper – Eshbaugh will have between 40 and 70 hours in each bow.