Crossing out luck

Skill key component in Cross Lake championship duel

Before the Wal-Mart FLW Tour Championship cast off on Cross Lake last week, it looked as if luck would play a large role in the tournament’s outcome. Between the bracket format, the stringent slot limit and the miserly fishing conditions, Lady Luck had a lot of opportunities to cast her own fickle whims.

Perhaps the outcome of the FLW Tour Championship would have been different without the slot limit or bracket format. But looking beyond the constructs of the event, it appears that skill was more of a factor than luck at the FLW Championship.

A close examination of John Sappington’s and Gerald Swindle’s patterns reveals that these two anglers were onto something very specific. Sappington and Swindle caught nearly identical weights on days one and two. They were the only anglers to break the 10-pound mark on day three, and both had the biggest creels on day four.

Pure luck? Hardly.

Despite the unconventional brackets and slots, the FLW Tour Championship on Cross Lake provided strong testimony that there is much more to bass fishing than luck.

Take 48 of the nation’s best bass pros, put them on a tiny, heavily pressured fishery in the middle of September, and catching bass becomes a kind of science fair project where hundreds of bass-fishing theories are tested cast by cast.

Imagine thousands of bits of information being fed into a large bass-fishing computer. Though this computer had a bracket format and a slot limit, it still yielded answers to every angler’s burning question: what are the bass doing?

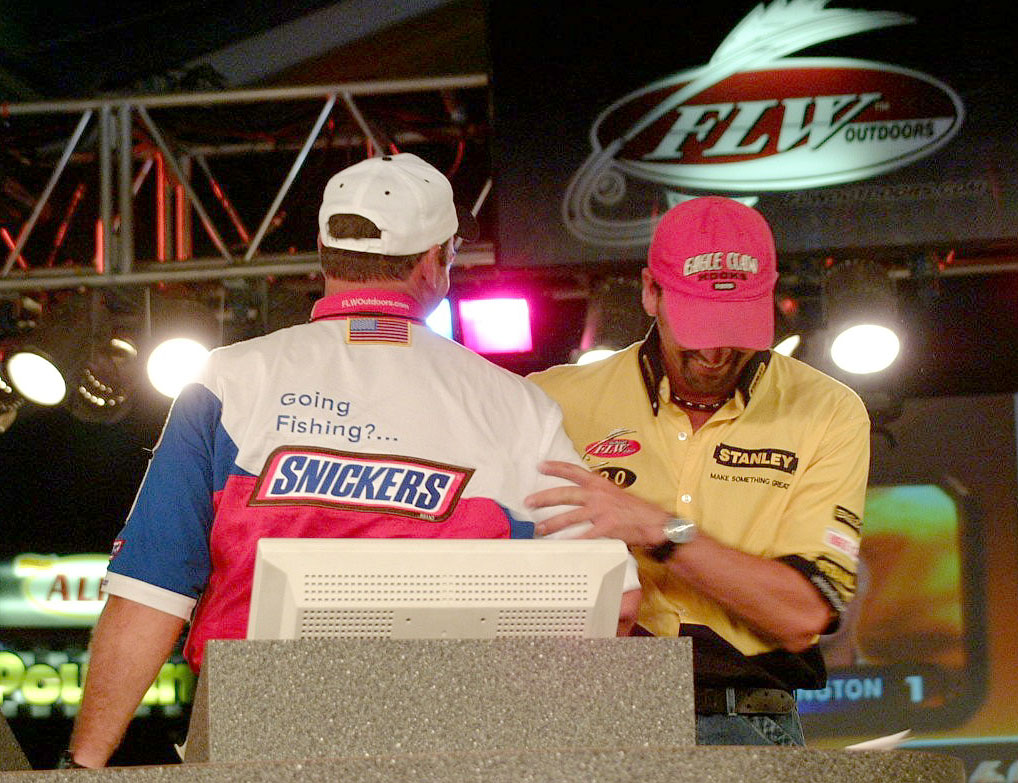

First place angler John Sappington and runner-up Gerald Swindle uncovered those answers on Cross Lake. Before the final day kicked off, both anglers were extremely confident in their findings.

First place angler John Sappington and runner-up Gerald Swindle uncovered those answers on Cross Lake. Before the final day kicked off, both anglers were extremely confident in their findings.

“I am dialed into exactly what to look for,” said Swindle without hesitation. “I can just about call my shots.”

Sappington said, “I don’t want to call it easy, but I have pretty much got (the bass) pegged.”

Those are strong statements coming from two anglers fishing for $260,000 on a shallow, heavily fished pond during Louisiana’s dog days of summer. Here is a close-up look at what these two anglers discovered.

Swindle’s docks

Swindle’s Cross Lake pattern revolved around docks. By committing his entire practice and tournament to docks, he eventually defined an undeniable dock pattern.

“The best docks were the shallowest docks,” said Swindle. “On days three and four, I didn’t waste time on deeper docks. I fished the shallowest ones I could find. When I ran out of shallow docks, I fished the shallowest parts of the semishallow docks. Sometimes my trolling motor would bottom out, and I would pitch up in there even shallower.”

The second critical component of Swindle’s pattern was that there had to be something in the water other than just pilings. Swindle’s eyes scanned under each dock for anything out of the ordinary.

“A metal pole next to a piling, a crossmember, a ladder, PVC poles, even a minnow bucket floating in the water – anything different,” said Swindle. “Standard pilings were unproductive. If there was something else next to a piling, it was an automatic fish.”

“A metal pole next to a piling, a crossmember, a ladder, PVC poles, even a minnow bucket floating in the water – anything different,” said Swindle. “Standard pilings were unproductive. If there was something else next to a piling, it was an automatic fish.”

To probe each dock’s eccentricities, Swindle pitched three different baits: a Zoom Centipede, a Zoom Brush Hog and a Yamamoto Senko – all in green pumpkin. He Texas rigged each bait with a 3/16-ounce weight tied to 25-pound test P-Line.

“I used the same size weight on each bait because I did not want to get out of rhythm,” added Swindle. “I was using all three baits interchangeably, and I wanted each one to feel the same on the end of my rod.”

Sappington’s cypress

Cypress trees were the most popular fishing objects on Cross Lake during the championship. According to anglers, it was not uncommon to see some of bass fishing’s most notable powerhouses fishing within casting distance of each other in the cypress stands.

On the first morning of the event, Larry Nixon, Dion Hibdon, Randy Blaukat, Jay Yelas, Gary Klein, Tommy Biffle and first-round leader Greg Hackney reportedly all began fishing the same area.

Sappington was in the fray as well. Sappington says the area was attractive because it offered deeper water adjacent to several shallow fields of vegetation. The cypress stand also contained something Sappington particularly liked: cypress tree points.

“One of the first things I learned in practice was that the fish seemed to be on cypress tree points,” said Sappington. “But instead of running the whole lake fishing cypress points, I decided to stay put in this one area because seven of these points came together in one spot.”

Sappington’s defined area was as big as half of a football field. He committed to it for all four tournament days. With each pass through the area, he became increasingly familiar with its underwater inhabitants and the pressure that was being put on those inhabitants.

Sappington caught his first day’s limit pitching a Limit Out jig to cypress trees. He noticed that many of his competitors were pitching trees, too.

On the second morning, Sappington pulled out one of his special homemade crankbaits carved by Tim Hughes Custom Crankbaits in Reed Springs, Mo.

He caught an over-the-slot fish immediately, which tipped him off to a crankbait bite. For the next three days, he cranked the handmade balsa plug around cypress trees to uncover a Cross Lake secret.

“That crankbait is a shallow-running bait,” explained Sappington. “If you hold the rod tip up high, it will run about a foot under the surface; if you hold the rod tip down on the water, it runs two or three feet. I found it was critical to hold the rod at just the right angle to make the bait dive to an exact depth. Holding it up high or down low was unproductive.”

In Sappington’s mind, the fish were suspended on the trunks of the trees, and the crankbait had to pass within several inches of their face to get a bite. On the first morning, Sappington claimed that several fish actually “moved the line,” and he even snagged one in the back.

He said: “That told me the fish were there, but my bait was diving too deep. The line was contacting the fish and spooking them before they saw the bait. When I started raising the rod tip at a certain angle to force the bait to swim higher in the water column, it was like turning on a switch – I really caught them.”

Sappington contends that there was something about the wiggle of his handmade crankbait that appealed to Cross Lake bass.

“Before coming out here (to Cross Lake), I tuned about 50 crankbaits in a pond at home,” he explained. “That particular bait was perfectly balanced; it wobbled perfect. I told my son that I would win a lot of money on that bait, and I saved it especially for the final round of competition.”

On the final morning of the tournament, Sappington quickly caught four fish on the coveted crankbait.

“I had my four keepers by eight o’ clock,” said Sappington. “Then, by accident, I slammed that crankbait into the passenger console and broke it. I never got another bite the rest of the day. I had some other crankbaits like it, but they did not produce like the one I broke. Maybe it was the bait, or maybe it was just in my head, but they quit biting after that.”

Fortunately for Sappington he already had the winning string in his livewell.

Perhaps Lady Luck smiled his way.