Correia’s chronicles

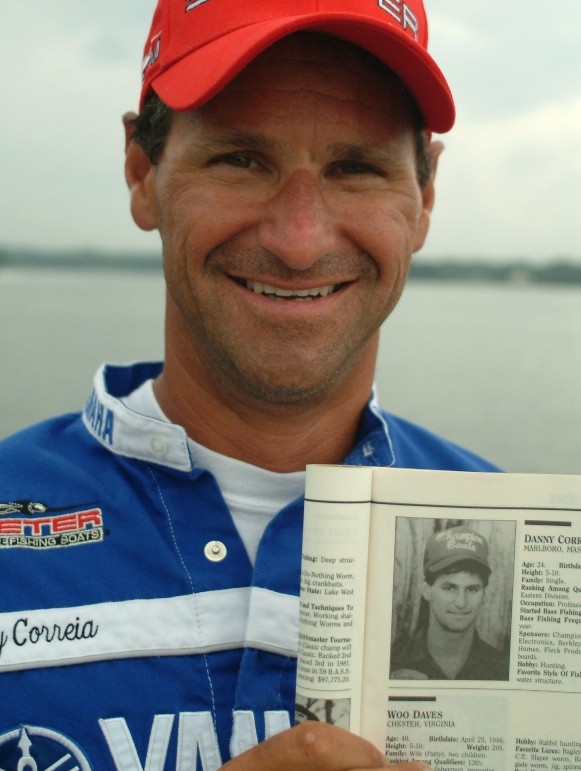

2006 Wal-Mart FLW Tour contender Danny Correia recounts 20 years of professional fishing as he prepares for season-ending tour event on Logan Martin Lake

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – As 48 of the nation’s best professional anglers take off from the Pell City Landing on Lake Logan Martin Wednesday morning for the start of the Wal-Mart FLW Tour Championship, Danny Correia of Marlborough, Mass., will be one of the hopeful competitors with his eye on the $500,000 payday.

This is not Correia’s first championship experience, though. Twenty years ago this month, Correia competed in the 1986 Bassmaster Classic on the Tennessee River at the age of 24.

Since then, the affable angler has lived the ups and downs of a bass pro and has enjoyed a front row seat to the myriad changes that have swept over the sport along the way.

Recently, while practicing for the FLW Tour Championship, Correia recounted some of his more memorable experiences during his early days on tour and made some astute observations about the modern state of the sport he loves.

The 1986 Classic

In many ways, Danny Correia was an anomaly to professional bass fishing in 1986.

Given bass fishing’s rich Southern tradition, “the kid with the funny accent,” as he was dubbed, stuck out like a Cape Cod saltbox on an Alabama farm at the Classic in 1986.

But his big grin and risible personality quickly earned him favor with his peers south of the Mason-Dixon Line, and to this day, Correia is still a sought-after character when a little comic relief is needed on tour.

Correia qualified for the 1986 Classic as a Federation Angler through his hometown club called the Greenwater Wizards, which is still in existence today. And he almost pulled off the unthinkable by nearly winning that very Classic as a rank novice from New England, finishing second to Charlie Reed by 13 ounces and winning $13,000.

“I was so clueless back then,” Correia laughed, looking back on the experience. “I literally read about this new technique called `flipping’ in a magazine about two weeks before that Classic. I had never flipped before and didn’t even own a flipping stick. So I ordered a few flipping sticks from Berkley just before the tournament and finished second by basically dunking a Gator-Tail worm with a 3/16-ounce weight on 14-pound-test line along edges of matted grass. But, hey, in my mind I was flipping.

“These days, I couldn’t imagine fishing a professional tournament with a technique that I had absolutely no experience with.”

First bass boat

In 1982, Correia was one of the first anglers in his area to own a “real” bass boat.

“It was a sparkly, metal-flake Ranger 350V with a 150 H.P., `loaded’ with two flashers and a paper graph,” he said. “When folks around home saw me at a gas station they would ask, `Where are the boat races?’ because they didn’t know what a bass tournament was.”

Hard times

Correia hit the BASS Tournament Trail in 1987. He quit his job as a computer instructor with Prime Computers and took up “banging nails” for his uncle’s construction business to make ends meet between tournaments.

His carpentry skills came in handy as he traveled the country on tour.

“I was probably the only guy on the circuit who carried a hammer and a complete set of power tools,” he said. “I had friends across the country who owned real estate or were building houses, and in between tournaments, I’d do odd carpentry jobs to make enough money to get to the next tournament.

“I never really made any good money in fishing until the last few years. I scraped by tournament to tournament for 15 years. Those were hard times, but looking back on it, it was a blast. I’ve fished all over the country and had some great times with some great people.”

Cost cutting and cockroaches

In order to afford tournament bass fishing in the early days, Correia and about a half-dozen fellow competitors would share a single hotel room to cut costs.

“We’d drive around until we found the rattiest place around,” he said. “Then we’d pack all of us into one room. It was brutal, but if you divide $29.95 a night by six people, we could stay in a place all week for about 30 bucks.”

It was through this cost-cutting process that “the kid with the funny accent” learned about roaches.

“Some of us – actually, most of us – would have to sleep on the floor,” he explained. “Where I’m from, we don’t have those giant cockroaches like they have in the South. The first night one of those gigantic bugs crawled across my face, it freaked me out so bad I had an absolute seizure.

“Where I’m from, we don’t have those giant cockroaches like they have in the South. The first night one of those gigantic bugs crawled across my face, it freaked me out so bad I had an absolute seizure.

“From that point on, I `d take a bed sheet and make a kind of hammock by tucking it into the mattresses around me, the nightstand or whatever was up off the ground to keep those huge bugs from crawling on me.”

Electrical hazard

The biggest issue Correia and his clan faced when sleeping so many to a room was charging boat batteries. Most roadside “roach coaches” didn’t have outside electrical outlets, so the crew would run five or six extension cords through the windows and doors.

“Needless to say, we didn’t watch much TV or have much light in the room at night because we had to use every outlet in a room to charge batteries.

“A lot of times we couldn’t close the door because of all the cords running out of the room. So we’d sleep with the door cracked. The idea of burglars didn’t bother me near as bad as the thought of more cockroaches getting into the room.”

Getting busted

Another challenge the penny-pinchers faced was keeping the motel owner from knowing that so many people were packed into a “single” room.

“Once, when checking out, the motel owner presented us with a complete list of every guy’s name that was staying in our room and then doubled our rate. When I asked how he knew all our names, he said he went into our room while we were gone and copied them down off our tournament jerseys, which were hanging up all around the room.

Delayed billing

Another trick Correia employed during the good old days of mechanical credit card imprint machines was to seek out gas stations that could not wire credit card debits electronically.

“It didn’t take me long to realize that gas stations which used the old imprint machines could not verify your credit card balance immediately. If I knew my card was maxed out, I’d go out of my way to find filling stations out in the country that used an imprint device so they wouldn’t know my balance.”

Regarding maxed-out credit cards, Correia noted that in those days, credit card companies didn’t have the astronomical $10,000 to $15,000 limits which are common today.

“The credit card I had back then `maxed out’ at a thousand dollars, so it’s not like I was running some out-of-control balance on my card. I never let myself go into debt fishing. I always paid off my balances, even if I had to do it by banging nails.”

Increased fishing pressure and information

Interestingly, of all the changes that have affected professional fishing over the last two decades, Correia points to the combination of faster dissemination of information and increased fishing pressure as being the biggest.

“Back when I started fishing, the learning process was so slow,” he noted. “Before the Internet and televised tournaments, it took new fishing techniques a very long time to trickle down through the masses.

“That’s why guys like Roland Martin, Denny Brauer and Shaw Grigsby would get on such dominating rolls for months at time. Not only were they great fishermen, but they could keep detailed winning techniques like flipping or sight-fishing to themselves for a much longer period.

“These days, a pro wins a tournament on a Senko, the next day it’s all over the Internet, the next week it’s on national TV and within weeks everybody is fishing a Senko on their home lake.

“So not only are there way more people fishing seriously for bass now, but the average bass angler is a whole lot better today than they were 20 years ago, thanks to better equipment, technology and information.”

Correia contends these two points come together to create a new fishing reality: Bass are getting smarter.

“Being a good fisherman is not so much about dominating with one technique any more; it’s about staying educated on the latest trends, getting comfortable with them quickly and employing them before others. Tournament bass fishing is now a huge race for latest thing that bass haven’t seen.”

As a result, he believes the trend toward finesse fishing is only going to continue.

“When was the last time a tournament was won on a crankbait or spinnerbait?” he questioned. “These days it’s all about natural-looking stuff – jigs and soft plastics – that’s what’s putting tournament checks in the bank.”

“When was the last time a tournament was won on a crankbait or spinnerbait?” he questioned. “These days it’s all about natural-looking stuff – jigs and soft plastics – that’s what’s putting tournament checks in the bank.”

The drop-shot rig alone is largely responsible for a huge turnaround in Correia’s career.

“I used to be a die-hard spinnerbait fisherman, and for 15 years I barely broke even chucking a spinnerbait. In 2001, I picked up a drop-shot and immediately won a tournament with it (BASS Open on Lake Martin). I’ve made more money with a drop-shot in the last five years than I made over the last 15 years with a spinnerbait.”

Fierce competition

When Correia started fishing professional tournaments, a full field was 100 to 150 boats with a limited three-day practice.

These days, FLW Outdoors bass events generally fill fields to 200 boats, and the FLW Tour and Stren Series events have unlimited practice.

“Tournament bass fishing has always been fiercely competitive, but nothing like it is today. Having been conditioned to a three-day practice for so many years, it amazes me to hear about these guys who go to a lake for 15 days before an event. By the time the tournament starts, these guys could be considered locals.

“But that’s the evolution process for this sport: Fierce competition leads to new lures and techniques to outsmart bass; those innovations debut as effective bass catchers in tournaments; the information spreads through the Internet and television; everyone starts catching fish on it across the country; the bass get conditioned to it; something new comes along, and the whole cycle starts over again.

Payouts, costs and sponsors

One of the most obvious changes in the sport of professional bass fishing in the last 20 years has been the extreme increase in payouts.

While 50th place paying $10,000 has become the new standard in professional events, Correia remembers a time when fifth place in a pro event didn’t pay that much.

“There’s no doubt that payouts in bass fishing are the best they’ve ever been,” Correia acknowledged. “But traveling the tours is also much more expensive than it was 20 years ago, too.

“Gas used to be a dollar and a half a gallon, an entry fee into a BASS Invitational was around $400 and, like I said, lodging was virtually free. I can remember several years in my early days where I fished the entire BASS season for about $6,000 total.

“So it’s all relative, but the winnings-to-cost ratio has improved drastically for me over the last five years, much of which is due to the FLW Tour’s $10,000-to-50th payout. And much of that is due to the healthy influx of nonendemic sponsors that have entered the pro fishing scene over the last decade.

“Twenty years ago, pros were all competing for the same 15 sponsors – the major manufacturers of boats, motors and tackle were always tapped out.

“Nowadays, there are gas companies, candy companies, drink companies – you name it – getting on board. And fortunately for all of us, it’s had a collective effect – more companies have wanted in to see what this is all about.

“Twenty years ago you were wasting your time pitching an insurance company or telecommunications company on a fishing sponsorship, now it’s totally in the realm of possibility, not only to make the pitch but also to get the deal.”

A better time

An examination of Danny Correia’s career over the last 20 years reveals an  interesting fact: Three-quarters of his total career winnings on both circuits have come in the last quarter of his career.

interesting fact: Three-quarters of his total career winnings on both circuits have come in the last quarter of his career.

Last year on the FLW Tour, Correia earned $55,000 in winnings, not including the money collected from undisclosed incentives in his sponsor contracts.

This year, pending his finish in the championship, looks to be even better.

“It’s a combination of all the things we’ve talked about,” he offered as a reason for the turnaround. “Everything from better payouts to fishing smarter with techniques like the drop-shot have all helped me turn the corner and show a nice fishing profit over the last few years.”

And there are no more scary, roadside motel incidents, either. Like many other pros these days, Correia stays in lakeside campgrounds in a comfortable travel trailer that he and fellow FLW Tour pro Pierre Fortin share.

“I like the camping deal; it’s far more relaxing,” he said with a final chuckle. “And I don’t have to fight for a night’s sleep against five snoring guys on a moldy floor full of roaches with 600 volts of electricity running by my head.”